Episode 8, Season 1

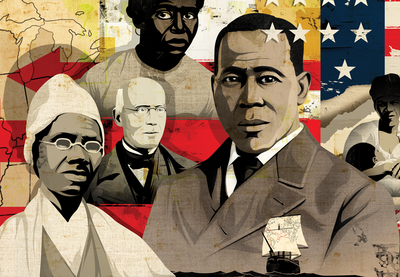

Film has long shaped our nation's historical memory, for good and bad. Film historian Ron Briley offers ways to responsibly use films in the classroom to reframe the typical narrative of American slavery and Reconstruction.

Earn professional development credit for this episode!

Fill out a short form featuring an episode-specific question to receive a certificate. Click here!

Please note that because Learning for Justice is not a credit-granting agency, we encourage you to check with your administration to determine if your participation will count toward continuing education requirements.

Subscribe for automatic downloads using:

Apple Podcasts | Google Music | Spotify | RSS | Help

Resources

- Learning for Justice, Exploring Diversity and Stereotypes in Film

- Learning for Justice, Examining Multiple Perspectives in Film

- Teaching Hard History, Episode 9: Ten More: Film and the History of Slavery (podcast)

Ron Briley

- All-Stars and Movie Stars: Sports in Film and History

- The Ambivalent Legacy of Elia Kazan: The Politics of the Post-HUAC Films

- The Baseball Film in Postwar America

- LA Progressive (articles)

Transcript

Hasan Kwame Jeffries: I have always loved the movies. Among my fondest childhood memories are trips with Aunt Shirley and Aunt Shelley to the old Kings Plaza Theater on Flatbush Avenue in Brooklyn. There, I left the borough behind to explore galaxies far, far away, and phoned home when I found the Lost Ark before traipsing through the Temple of Doom.

When I was old enough to go to the movies by myself, I always tried to do the right thing and not be a menace to society, so I stuck to house parties, where I had a little bit of juice, because I wasn’t just coming to America; I was straight out of Brooklyn. After my school days at Morehouse, I spent more than a few dead presidents waiting to exhale on a Friday, chasing a love jones, but settling for some soul food with my best man at the barber shop. So, it should come as no surprise that my favorite class to teach is African-American history through film.

My film class covers the black experience from slavery through the present. Once a week, we meet at a theater on the outskirts of campus and watch a major motion picture. The last time I taught the class, we started with 12 Years A Slave and ended with Moonlight, and in between, we screened everything from Amistad and Glory to Fences and Fruitvale Station. These movies make the black experience come alive, adding depth and dimension to the famous and the forgotten, to the extraordinary and the everyday. They help students imagine the seemingly unimaginable; generating empathy by capturing and conveying deep emotion.

As much as my students enjoy these films, they alone are not enough to teach them to think critically about popular portrayals of hard history like American slavery, so I pair every movie with documentary films. Sometimes, three and four a week. I found that students who resist reading 20 minutes a night will watch a two-hour documentary in a heartbeat.

In the past, I’ve put 12 Years a Slave together with Unchained Memories, and Glory with The Abolitionists, and have paired both of these films with episodes of Africans in America. Doing so provides students with critical background information. It also challenges their basic assumption that what appears on screen must be true. This happens when what is discussed in a documentary, such as women’s resistance to slavery, fails to show up in a movie about enslaved resistance, such as the Birth of a Nation.

The old Kings Plaza Movie Theater on Flatbush Avenue closed not that long ago after a 40-year run, but the memories of my outings there are as vivid as ever, because that’s where I learned to love the movies, and that’s also where I learned about the power of film.

I’m Hasan Kwame Jeffries, and this is Teaching Hard History: American Slavery. It’s a special series from Learning for Justice, a project of the Southern Poverty Law Center. This podcast provides a detailed look at how to teach important aspects of the history of American slavery. In each episode, we explore a different topic, walking you through historical concepts, raising questions for discussion, suggesting useful source material, and offering practical classroom exercises.

Talking with students about slavery can be emotional and complex. This podcast is a resource for navigating those challenges, so teachers and students can develop a deeper understanding of the history and legacy of American slavery. For students to get the most out of movies in the classroom, they need to be able to understand what they are watching. How does a depiction of slavery onscreen compare to historical reality? What does this tell us about the time period the film was made? In the end, students need to be able to ask and answer, “How does a particular film help us better understand American slavery?”

In this episode, Ron Briley shares ideas for incorporating movies into your lesson plans. He recommends specific films that will allow you to explore topics from the Middle Passage to Reconstruction. He also suggests pedagogical techniques, such as using primary source material to help students critically analyze those films. I’ll see you on the other side. Wakanda forever.

Ron Briley: I’ve employed film in the classroom now for almost 40 years, and I’ve found it an incredibly rewarding experience. When I talk to students many years later, it is often what they remember the most from the classroom and the discussions surrounding these films, and I’d like to share with some of my fellow teachers some of those challenges and excitement of using film, especially to teach a controversial, important topic such as American slavery.

First, let me just mention, before we look at some specific films, some of the reasons for using film in the history classroom, both documentaries and feature films. First of all, for better or worse, as much as we might want students to read, unfortunately, many students learn their history through film, and thus I think it’s essential to bring film into the classroom. We might wish that they would be reading the leading historical monographs, reading scholarly journals. Instead, like most Americans, they’re going to be watching movies.

So, I think what we need to do as teachers is sort of accept that fact, and then, I think it’s important to learn some critical viewing skills and how to ask questions of the material that they’re watching. What I hope is that by using film in the classroom, this will encourage students to dig deeper and to actually do some reading assignments, and I usually give bibliographies and make suggestions as to how students can then further pursue the topic that’s been introduced through film.

Another really good aspect of film is that it introduces empathy, and I think this is so important for our students. It’s different sometimes, seeing it on the screen. Let me do a quick example. Say The Grapes of Wrath, for a moment. Wonderful book that really depicts in so many strong ways the travails of the Joad family in America during the Great Depression. However, seeing a film clip from John Ford’s The Grapes of Wrath seems to drive this home even better than Steinbeck’s wonderful text. Hopefully, students would look at both, but I think the idea of the film brings such empathy, and I think that in a controversial, emotional topic such as American slavery, this is an important contribution that film can make.

Another really good aspect for using film is, when you’re looking at a film in the classroom, it’s not just the subject on the screen that you’re looking at, but you’re also looking at the values of the time period in which the film was made, how especially feature films reflect the time period in which they were made. They reflect the values of that period. Thus, a film dealing with American slavery, if it’s made after the civil rights movement, it’s often going to have a very different perspective than one that was made before the civil rights movement. So, I think you really have to look at how the values of the time period in which the film is made are also reflected on the screen, and I think that is something very important that film brings to the classroom.

Then of course, with a topic like American slavery, and probably using film in general, you’re going to get complaints sometimes from parents. On one level, it goes with the territory, especially when you teach and have the courage to teach controversial subjects. I think if you look at some of the reasons for teaching film that I’ve outlined here, and, I think, present them to the parents, I think you can win most of them over. I’ve certainly found that to be true in my teaching career, but I think film is too important to not be employed in the classroom. Again, I would really encourage teachers to use film in tackling a subject such as American slavery.

Now, obviously for an emotional subject such as American slavery, you need to very carefully prepare the students for what they’re about to see. Doesn’t mean they will necessarily be comfortable with it, but you don’t want to shock them. You want to prepare them. And, in terms of using film, preparation is essential. Of course, there are some very negative stereotypes about using film in the classroom. It’s a Friday afternoon, everyone’s tired, and you just simply put on the film and everyone just kind of takes the afternoon off.

Well, film is much more important than that, and teachers need to carefully prepare films that they’re going to use in the classroom. For example, an English teacher would not teach a book they had never read before, and I think the same thing is true for history teachers. If you’re going to use a film in the classroom, you can’t just put it up there and expect students to watch it and get something out of it. You have to very carefully screen the film first, be very familiar with the film text.

I think that preparation in regard to films is essential, and also, I think there are a few other things in regard to teaching film. I think there’s a tendency sometimes to get overly hung up on the details. Is this exactly the right uniform in a military film? You can get hung up on that sort of thing, and sometimes lose sight of the larger historical issues and truths. I think most filmmakers try to get this right, but that’s really not the thing to focus on in the classroom. It’s really these larger historical truths that are essential to engage our students.

Also, especially when using feature films, teachers need to realize that in order to tell a story within a two-hour format, it’s very important for the director, the filmmakers, to compress time, to fit it within these two hours. Also, you sometimes have to use composite characters to do this, and you don’t want to falsify history, but I think sometimes in looking at films, there’s a tendency to be overly critical of filmmakers when they don’t follow every historical detail. I think that teachers need to point this out, and students need to be educated in that regard so they continue to focus on the larger historical truths that the film is trying to get across about a subject such as American slavery.

Another aspect is time. Time is a huge consideration. Always, always crucial in the classroom. It would be wonderful if you had the time to screen an entire film, but most teachers do not have the time to show a two-hour film. Maybe occasionally you do, but most of the time, that’s not going to happen. So, what you really need to do is carefully pick out film clips. A 10, 15, probably tops-20-minute clip from the film. Students have to be introduced very carefully, prepared, say, with characters, what’s sort of going on in the plot. You need to very carefully set up that selected film clip to raise some of the points you would like to raise with the class. But it’s very important to set the context for those clips that you’re going to use.

In selecting a clip, first of all, you need to screen the film carefully, okay? That’s the first step, and be taking some notes. Think about, maybe, what are the themes that you would really like to raise with your students from this film? And look at a clip that really brings these issues to the forefront. For example, in Gone With the Wind, there is the character of Mammy, a former slave woman who is the mammy to Scarlett O’Hara, has looked after her, brought her up since she was a child, and has been like almost a mother to her.

You can pick a scene with her interaction with Miss Scarlett, and you can raise a lot of questions about the roles of women, the roles of black women, especially black women in slavery. Some of the incredible inconsistencies with slavery. How a system based on this idea of racial discrimination, inferiority then places the training of their own children in the hands of black women. Things like that can be brought out. I think it depends on what it is that, as a teacher, you’re wanting to illustrate, that you want to draw out of the film. There’s probably a lot of different issues that you could raise. Maybe look at what you think will resonate best with your students.

And then last but certainly not least, in this era in which we hear so much about fake news and people being misled by items on Facebook, et cetera, it’s so essential that we endow our students with critical viewing skills and ask difficult, challenging, critical questions of images. I think that a serious engagement with film in the history classroom is simply something we must do in order to prepare better citizens. So, for all these reasons, I think film offers a wonderful opportunity for teachers, and really is essential in the classroom.

An area where we might look at employing film in the classroom and how feature films have really influenced how we view a period is in the teaching of Reconstruction, and I think in teaching Reconstruction, you must relate that to slavery, because I think the popular perception of Reconstruction is a rather negative one. Historians such as Eric Foner have done a great job in recent years of trying to change how we perceive Reconstruction; to view Reconstruction as a great experiment, a biracial coalition seeking to promote racial understanding, trying to overcome the burden of slavery.

But instead, Reconstruction is often viewed, as author Claude Bowers put it, as the “Tragic Era,” in which the South was taken advantage of after the war by free blacks, northern carpetbaggers, the freedmen former slaves, and poor southern whites. Popular culture has often presented Reconstruction as a travesty in which white southerners were treated terribly till they rose up and redeemed the South and retook control. That is the myth of Reconstruction, and it has certainly been perpetuated by Hollywood.

I think it’s very important to look at Reconstruction because presenting Reconstruction this way, as former slaves, blacks, out of control, ends up providing a justification of slavery. In addition to the economic aspects of slavery, certainly racial control was part of the institution of American slavery, and therefore, it’s very important that this stereotype of Reconstruction be challenged as historians like Eric Foner have done.

What I would like to do is talk about some specific examples. This sort of myth of Reconstruction, which one still often finds in the history classroom and in some textbooks, has been perpetuated in films such as Birth of a Nation from 1915 and Gone With the Wind from 1939. These two pivotal films really present the negative stereotype of Reconstruction, which has permeated American popular culture, and to a great extent, American politics throughout the 20th century and into the 21st century.

Let me talk about using these two very controversial films, clips from them, in the classroom. The first one that I would like to talk about is Birth of a Nation, made in 1915, by director D.W. Griffith. The film is still shown in lots of film classes. It’s well over three hours, dealing with the Civil War and Reconstruction. It introduced many important film techniques. It is a great work of art.

Unfortunately, that work of art perpetuates racist ideas, attitudes and stereotypes, and thus, you have to very much prepare students for this. The clip that I like to use, one I think really works best, is sort of the last 20 minutes of the film. Again, it’s a well over three-hour film. So, what’s occurring at the end of the film that the teacher would want to set up is, you have two families. The Cameron family is a southern family, again, white family. The Stonemans, a northern family. The senior member of the Stoneman family is a radical Republican. Sounds like a strange term today. It’s a radical Republican who wants to institute racial equality in the South, and he has raised to prominence in the South a black man named Silas Lynch. Interesting choice of words for the character.

What happens is, Silas Lynch reveals that he wants to marry a white woman, and Stoneman seems okay with this till he finds out that the woman that Silas Lynch wants to marry is his daughter, Elsa. This sets off the entire conflict here, where Elsa is taken captive, the father is taken captive in town; meanwhile out in the countryside, freed blacks are taking over and attacking a cabin in which the Stoneman and Cameron families, other members of the family, have taken refuge.

Things look bad. Again, the emphasis here is that what the blacks want to do is break in, attack, and rape the white women. So, who’s going to ride to the rescue? In this film version, the Ku Klux Klan rides to the rescue and saves the day. The South and southern virtue is symbolized by the women who are rescued from the clutches of the blacks, and the Klan is viewed as the hero, and then the film concludes with the white families from the South and the North are reconciled while the film actually shows the 15th Amendment being openly violated, and blacks being refused the right to vote, and somehow, the North and South is reconciled with blacks once again put in their place.

Incredibly racist material based on a novel and a play by Thomas Dixon, who just also happened to be a good friend of President Woodrow Wilson. Now, the way the Klan is shown is, by today’s standards, it’s almost laughable. One has to be very careful and set this up that the students watching this really don’t laugh at this. This is very serious business, because what actually happened in America in 1915 is Americans went to the theater. Many whites saw this. Racial violence in the country increased. Lynchings increased.

What students need to realize is, what might seem somewhat ludicrous on the screen now very much influenced events in 1915 and encouraged discrimination, violence against black Americans. So you’re looking at the racism of Reconstruction perpetuated into the progressive era of 1915, when the film was made. The film was very popular. Blacks protested it. It was not actually taken out of circulation until World War I, when there was a feeling that you needed black support for the war effort. In many states, the film was withdrawn after three years.

This is a very important source to introduce to students, but also, a very troubling source. Very complicated issues. Challenging issues to deal with in the classroom, but I think important issues to deal with. The sexual politics of slavery, of Reconstruction, are very important topics, and they do resonate with students. It’s interesting that the director, D.W. Griffith, didn’t think the film was racist, even though he said that he did not want black men touching white women in the filming of Birth of a Nation. So therefore, as ludicrous as it might seem, actually, almost all of the blacks in the film are played by whites, using shoe polish and blackface.

A very troubling moment in American history. However, in many textbooks, many teachers, presentations, this stereotype of Reconstruction has been perpetuated. And it continued with the very famous Gone With the Wind in 1939, and I use Gone With the Wind after we have screened the Birth of a Nation. The first half of the film is set in slavery; the second half of Gone With the Wind deals with Reconstruction, and Gone With the Wind is a little less over the top in its racism than Birth of a Nation. The NAACP insisted that use of, for example, the N-word, be taken out of the film, and actually, the Klan is not mentioned by name, but is certainly alluded to.

I think there’s particularly one scene there that I would like to talk about, that teachers might employ in the classroom. Let me spend a few minutes talking about that scene in Gone With the Wind. I think a useful way to view Gone With the Wind, and especially its heroine, Scarlett O’Hara, is to see Scarlett O’Hara as a symbol of the South. She is under attack in the film as the South was under attack during Reconstruction. I don’t use these words lightly, but in this stereotype, you’re really sort of looking at the rape of the South by poor southern whites, carpetbaggers from the north, and freed blacks. The saviors of the South? The Ku Klux Klan, again.

In the particular scene that I would use from the second half of the film, you have Scarlett O’Hara who has married a man by the name of Mr. Kennedy, and she has worked with him, and they’ve set up a lumber company. After the Civil War here, she has a very successful business. What happens is that she takes a shortcut while driving in her buggy, a shortcut through a shantytown. Living in the shantytown are a lot of poor whites and freed blacks. What happens is they attack Scarlett O’Hara, okay? And it looks as if she is about to be raped. She passes out.

She is rescued, however, by Big Sam, a loyal former slave from her plantation terra. He comes to her rescue and she is able to escape with Big Sam. She goes to her husband, who rewards Big Sam for his faithful service, and Big Sam says he’s had enough with these carpetbaggers. So, you haven’t shown actually northern carpetbaggers involved in the rape, but it’s very clear that they’re behind these freed blacks and poor southern whites.

Then, her husband says, “I’ll take care of this.” He says he’s going to a political meeting, and she needs to go visit her friends. By the way, it’s clear that this is not really a political meeting. The film emphasizes that he takes out his pistol, puts it in his holster, pats the gun. Clearly, he and his friends are going to go take revenge against the shantytown, and the political meeting he’s referring to really is the Klan, although the word Klan is not used in the film.

Then the film shifts to the women that evening, knowing that their men have gone out on this mission. Scarlett O’Hara doesn’t quite understand the total nature of the mission. However, Rhett Butler, a man she later marries, comes to see her and the other women, and wants to warn the white southerners that the Yankee troops are waiting in ambush. Butler, however, does not get there in time, and the ambush is completed, and Scarlett’s husband is killed. However, they did succeed in burning down the shantytown.

Again, the bad guys are the northern troops, the freed blacks, except for loyal former slaves like Sam, and this is all orchestrated by the carpetbaggers. But again, this view of Reconstruction very much perpetuated in popular culture, from Gone With the Wind down to the present.

I’m older. I went to school in the 1960s, and this was very much the view of Reconstruction that I was taught, and I still see it throughout our culture. So, I think using these films to look at how cultural stereotypes are established are very important, and encouraging students to challenge these types of cultural stereotypes. So, I think these two films looking at the myth of Reconstruction are very important to use in the classroom.

One of the things students notice is some of the difference between Gone With the Wind and Birth of a Nation. Still plenty of racial stereotyping, et cetera, but in many ways, the racist is less obvious, and students do note this. But nevertheless, they notice the connections between the two films. They notice how, oh, there seems to be a reference here to the Klan, but the Klan is not mentioned by name. They’re a terrorist organization that shall not be named, and they do pick up on these subtle differences. They pick up on these subtleties.

But what they also perceive, and they do a good job of this, of seeing, in many ways, how the film texts are similar. You still have this idea in both films of southern womanhood symbolizing southern civilization that’s under assault, and we have to protect southern womanhood. It also ties into discussion of the Lost Cause in the South, and many times leads us into discussion of Confederate monuments and how the memory of slavery, Reconstruction is molded in the American mind.

Again, I try to always bring in reading material on this that will expand these issues, and in terms of Confederate monuments, there’s a new book out by the New Orleans mayor, Mitch Landrieu, that raises many of these same issues in regard to confederate monuments. So, I think you can take these film texts and use them to take us right into contemporary, modern day discussions and subjects.

Now, I like to talk about two other feature films, and these feature films do a better job of bringing in black agency. That is the Steven Spielberg film, Amistad, and the Edward Zwick film, Glory. Let’s begin with Amistad. The film deals with a slave mutiny aboard a Spanish slave ship. What happens is, the mutiny is successful. However, after the mutiny, the ship ends up off the coast of North America, and the mutineers are taken in by the American government, and the question is, what to do with them?

Again, it’s important that the students understand that this is based on a true story and that the basic overall facts in the film are accurate, but there are a few caveats that we should take a look at. The film really focuses not so much on the revolt itself, but on the court case. What do we do with these slaves who have mutinied and have now been taken into custody by the United States government? The Spanish government wants them returned. Abolitionists take on the case and argue for the freedom of the slaves.

The film culminates in a series of court cases, but culminates in the arguments of John Quincy Adams, former president, who is now in the House of Representatives and played by Anthony Hopkins, in a role for which he was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor. It culminates in his argument before the Supreme Court, in which he basically appeals for the freedom for the mutineers and their leader, Cinqué. He says that they should be freed, and he uses primarily arguments from the Declaration of Independence. He appeals to the court using the arguments of people like Jefferson, even though he was a slave owner. His own father, John Adams, George Washington, also a slave owner. And what happens is, the court agrees, and the mutineers are freed and returned to their home in West Africa.

Now, there’s a couple of problems with the film. First of all, though, I would use it because it does show a sense of black agency, even though the emphasis is sometimes more on the court case than the actual mutiny. But one of the things that I think is very good to use with the film is, during the testimony, there is a flashback to the Middle Passage. Cinqué, through an interpreter, tells the story of what happened to his people in the Middle Passage. It shows the capture of Cinqué and many others, how they’re brought to a slave garrison, sold to a Spanish slave vessel, and there, the emphasis is then on the terrible conditions below deck.

One of the things that probably really stands out that’s very powerful is, as people get ill, they die, they throw people overboard, and they talk about actually sharks following the ship for these bodies that are going to be thrown overboard. When they think they’re going to be confronted by a vessel attempting to stop the slave trade, they have people in chains and simply throw them overboard, alive, to drown and to be devoured by sharks. It’s a very, very powerful scene. Again, I think the fact that it’s not simply told with someone just telling the story in a verbal fashion, but that it’s shown on the screen, really reinforces just the horror, well, the holocaust, of the transatlantic slave trade.

And you can read all you want to for students about the Middle Passage, but seeing this on the big screen, it’s graphic, it’s troubling, but nevertheless, I think very important for students to actually see this. So, I think the Middle Passage segment of the film is a very strong element to include in the classroom.

But something else that I would point out to students about the film is that, while it does show black agency in terms of the slave revolt and finally winning their freedom, Hollywood films often tend to emphasize the white characters. So in many ways, the center of the film becomes John Quincy Adams making his arguments before the Supreme Court, and the film tends to ignore the fact that the court, in setting these former slaves free, really was not so much using the Declaration of Independence in their reasoning. They were really talking more about property rights, which they wanted to be sure were protected. After all, this is the same Supreme Court that issues the Dred Scott decision later. Of course, that decision upheld that blacks were not citizens of the United States and therefore, there could be no restrictions legislatively put on slavery and declared them as a compromise, unconstitutional. I think that aspect needs to be pointed out in students evaluating the film; this tendency to often, even in films that are empathetic toward blacks, to still emphasize the white character.

Another film that shows black agency is Glory, and this film, again, got very good marks from historians. It tells the true story of the 54th Massachusetts regiment in the Civil War, and this was a black regiment. The North was reluctant to raise this regiment. Lincoln was reluctant. But pressured by people like Frederick Douglass, this regiment of black troops is formed, made up of free blacks from the North, made up from former slaves from the South, and they are commanded by a white Colonel Robert Shaw, who’s played by Matthew Broderick.

They present this regiment finally going into action in the assault against Fort Wagner in South Carolina, and the film very much does a good job of showing black agency as the troops want to fight for their freedom. This was not something that was just done by whites and handed to blacks. Instead, this was something that blacks took a very important role in, and essentially, the information on the attack is accurate. The attack was unsuccessful, and what you have, in a lack of respect afterwards, is sort of a mass grave in which the black troops were thrown in, their bodies.

Now, in terms of using this in the classroom, there are a couple of clips that you might use, okay? One scene that’s very powerful is how Colonel Shaw decides that he has to bring discipline to his black troops. One of them is a composite character by the name of Silas Trip, played by Denzel Washington, who won an Academy Award here for Best Supporting Actor in this role. In this particular scene, Matthew Broderick, playing Colonel Shaw, is trying to provide a sense of discipline for his black troops, and the character Silas Trip, played by Denzel Washington, who is a former slave with a rebellious streak who has run away and joined the Union army, has left the regiment without permission.

One problem for the 54th Regiment is that they lack supplies. They do not have shoes, and his feet are killing him. He’s not deserting. He is actually foraging, looking for shoes and food. When he is brought back, to instill discipline, Colonel Shaw says there’s no choice but to give him a lashing. As he is tied down to be lashed, his uniform is removed and his back is covered with scars from his experience as a rebellious slave, and you realize that he’s been beaten a great many times already as a slave, and now the Union army is also administering this beating. You can see the pain in Shaw’s face as he realizes now that he’s going to inflict more punishment upon Trip, and Trip does not cry out. Tears roll down his eyes, and the two men look at one another, and both men form a bond through this terrible scene, as actually, at the end of the film, they’re buried together in a mass grave after the unsuccessful assault on Fort Wagner in South Carolina. That’s a very, very powerful scene that one might use.

Another scene that one might use in the classroom is actually the final assault. Some have criticized the assault for perhaps celebrating violence. On the other hand, it is worth remembering that the terrible violence of the Civil War did achieve the end of slavery, and that’s certainly something to talk about in the classroom with your students. But the assault is, again, unsuccessful and in the end, you see Colonel Shaw, the white officer, thrown into this mass grave with the black troops.

It might be also worth pointing out that having black troops with a white commanding officer, that was really the standard for American Forces from the Civil War era down to World War II. That really, the American Army, American Forces, Armed Services, really only integrated by President Truman after an executive order, after the Second World War. It’s worth pointing out that for the black troops shown in the film, these are composite characters. Colonel Shaw is an actual historical character, and much of the film is based upon his letters to his parents back in Massachusetts, and these letters are often read in the film. Many times, the emphasis upon white characters also relates to the available sources as well as, to be honest, wanting the film to appeal to white audiences.

So, I would consider both Amistad and Glory feature films that present a sense of black agency. But, in terms of critical viewing skills, discussions might look at how whites remain privileged in these films. These are four feature films. There are many others. Also, excellent documentaries which one could use in the classroom. I think these four are ones that will appeal to students and introduce some very important ideas into the classroom. It’s challenging to present these images dealing with slavery. It can be controversial. But I think it’s incredibly worthwhile for what it provides students in terms of visual literacy.

I really encourage teachers to use film in the classroom. I’ve found it so rewarding both for me and for my students, and you know what? Film is a lot of fun in the classroom, too, and I think that’s allowed even when we’re dealing with some controversial subjects.

Hasan Kwame Jeffries: Ron Briley is a film historian who recently retired from Sandia Preparatory School in Albuquerque, New Mexico after teaching history for 37 years. He was also an adjunct professor of history at the University of New Mexico, Valencia campus for 20 years. Mr. Briley is the author of five books and numerous articles on the intersection of history, politics and film.

Teaching Hard History is a podcast from Learning for Justice, with special thanks to the University of Wisconsin Press. They are the publishers of a valuable collection of essays called Understanding and Teaching American Slavery. In each episode, we feature a different scholar to talk about material from a chapter they authored in that collection. We’ve also adapted their recommendations into a set of teaching materials, which are available at LearningForJustice.org. These materials include over 100 primary sources, sample units, and a detailed framework for teaching about the history of American slavery.

Learning for Justice is a project of the Southern Poverty Law Center, providing free resources to educators who work with children from kindergarten through high school. You can also find those online at LearningForJustice.org. Thanks to Mr. Briley for sharing his insights with us. This podcast was produced by Shea Shackleford, with production assistance from Tori Marlin and Megan Camerick at KUNM public radio. Our theme song is “Kerr’s Negro Jig” by the Carolina Chocolate Drops, who graciously let us use it for this series. Additional music is by Chris Zabriski.

If you like what we’re doing, please let your friends and colleagues know, and take a minute to review us in iTunes. We always appreciate the feedback. I’m Dr. Hasan Kwame Jeffries, associate professor of history at the Ohio State University, and your host for Teaching Hard History: American Slavery.

References

- John Ford, The Grapes of Wrath (film)

- Colonial Williamsburg Foundation: Slavery and Remembrance, Middle Passage

- Victor Fleming, Gone with the Wind (film)

- Claude G. Bowers, The Tragic Era The Revolution After Lincoln

- D. W. Griffith, The Birth of a Nation (film)

- Thomas Dixon, The Clansman: An Historical Romance of the Ku Klux Klan

- Steven Spielberg, Amistad (film)

- Mitch Landrieu, In the Shadow of Statues: A White Southerner Confronts History

- Learning for Justice: Texts, Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857)

- Edward Zwick, Glory (film)

- University of Wisconsin Press, Understanding and Teaching American Slavery

- Learning for Justice, A Framework for Teaching American Slavery