Episode 6, Season 1

To see a more complete picture of the experience of enslaved people, you have to redefine resistance. Dr. Kenneth S. Greenberg offers teachers a lens to help students see the ways in which enslaved people fought back against the brutality of slavery.

Earn professional development credit for this episode!

Fill out a short form featuring an episode-specific question to receive a certificate. Click here!

Please note that because Learning for Justice is not a credit-granting agency, we encourage you to check with your administration to determine if your participation will count toward continuing education requirements.

Subscribe for automatic downloads using:

Apple Podcasts | Google Music | Spotify | RSS | Help

Resources

- SPLC, Teaching the Hard History of American Slavery

- Teaching Hard History, A Framework for Teaching American Slavery

Kenneth Greenberg

- History, Suffolk University

- Honor and Slavery: Lies, Duels, Noses, Masks, Dressing as a Woman, Gifts, Strangers, Humanitarianism, Death, Slave Rebellions, the Proslavery Argument, Baseball, Hunting and Gambling in the Old South

- Nat Turner: A Slave Rebellion in History and Memory

Transcript

Hasan Kwame Jeffries: Soon after we launched this podcast, I received a direct message on Twitter from a middle school educator. The message began:

Izzy Anderson: “Good morning, Mr. Jeffries. I am a school librarian in the Arkansas Delta. In addition to being a librarian, I also teach a small gifted and talented literacy class, which is made up primarily of black sixth grade boys. My students do not get a full year of social studies at my school, so I’m modifying my curriculum to teach black history to my students this month, and probably for the rest of the year. I am starting with slavery, so I’ve been listening to your podcast for ideas.”

“I am a white educator, and I’m concerned about teaching history in a way that is honest and true, but avoids traumatizing my young students. My students live in an area of the country that, in many ways, is still experiencing the reality of Jim Crow. I think it’s really important for them to understand their own history, but I don’t want to do an information dump on them without also caring for their hearts. I’d appreciate any suggestions you might have, Izzy Anderson.”

Hasan Kwame Jeffries: I knew exactly where Ms. Anderson was coming from, both as an educator, and as an African American who had mostly white teachers in elementary and high school. I appreciated her candor and concern, as well as her commitment to teach more than what was required. So I messaged her back, “Hi Izzy, thank you very much for your thoughtful note. I suggest beginning the conversation in the present by explaining to your kids that you have to look to the past to understand current times. That will help get them interested, and don’t avoid talking about the harshness and brutality of slavery. No one who watches television is unaware of violence, but it needs to be explained that slavery was so brutal, because black people were constantly resisting in every way imaginable.”

“Explain to them how central slavery was to American growth, and you can’t emphasize enough that there is real pride to be found in this history, the pride of surviving a horribly unjust system, the pride of knowing their ancestors resisted, the pride of knowing that black people were right in their insistence that slavery was wrong, and the pride of knowing that the enslaved never gave up hope, they never surrendered their humanity. Be clear with them, too, about what was right and wrong, about who showed true strength and courage, and they’ll get it.”

It’s not going to be easy, as they will have a range of reactions and emotions, but affirm those feelings. Tell them, ‘Yes, this makes me mad too,’ and always redirect them toward drawing inspiration from the enslaved who endured, who fought, who survived despite all odds. Good luck.” Two days later I received another message from Ms. Anderson, an update on what had been going on in her class.

Izzy Anderson: “Thank you so much for such a long and thoughtful message. Since I’ve read it, I’ve been really leaning into letting students express their emotions as we read and learn.”

“What I didn’t expect is the amount of anger they are expressing. They’re angry, wondering, ‘Why haven’t I learned this before?’ and I think the anger is righteous. My job now is to help them express it constructively.”

Hasan Kwame Jeffries: “And that’s the thing,” I wrote back, “Your students’ reaction, their righteous anger, is consistent with the reaction of my students in college, both black and white. When they are exposed to the truth in a thoughtful and honest way, they get pissed off, but not at the truth teller, but rather at those who withheld the truth from them. Now you have to capitalize on that anger,” I said. “Use it as motivation for them to learn more about what others aren’t going to teach them. I promise, you will be the teacher who they will remember because you told them what others wouldn’t. Peace, Hasan.”

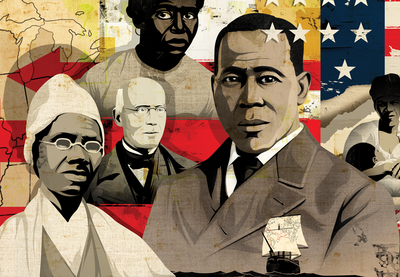

There is nothing more dispiriting to students than to think that the enslaved accepted their fate, so teaching resistance is the key to getting students to want to learn about slavery. Hard history, you see, is not hopeless history, and there is no greater hope to be found in those dark days than in African Americans’ resistance to slavery, and that’s what we’ll be exploring here. I’m Hasan Kwame Jeffries, and this is Teaching Hard History: American Slavery. It is a special series from Learning for Justice, a project of the Southern Poverty Law Center.

This podcast provides a detailed look at how to teach important aspects of the history of American slavery. In each episode we explore a different topic, walking you through historical concepts, raising questions for discussion, suggesting useful source material, and offering practical classroom exercises. Talking with students about slavery can be emotional and complex. This podcast is a resource for navigating those challenges, so teachers and students can develop a deeper understanding of the history and legacy of American slavery.

Our understanding of resistance to slavery in the United States has changed over the years. In this episode, Kenneth Greenberg explains the evolution from looking exclusively at instances of rebellion, to examining the numerous ways that enslaved African-Americans incorporated resistance in every aspect of their lives. He also offers several examples that you can use to explore resistance with your students, and stay tuned at the end of the episode for advice from Ms. Anderson for teaching these topics and techniques for the first time. I’ll see you on the other side, enjoy.

Kenneth Greenberg: When we talk about resistance to slavery, at first glance you might think this is a narrow topic, since slavery is such a big, big subject, but it turns out that you’re actually touching on every aspect of slavery. It’s the most probably revealing way of entering the subject. There is resistance during the entire time, from 1619 or so, when the first African-Americans are brought into Virginia, until slavery is officially legally ended in 1865. I think it’s important to have in mind that there’s a paradox at the heart of slavery.

Slavery is this horrific, exploitive, brutal institution on the one hand, and on the other hand, African American culture flourishes in the institution of slavery, survives the institution slavery, despite the brutality of slavery, and you want to teach both those things when you teach students about the institution of slavery. If you focus on resistance, you can teach both those things at the same time.

One side of slavery is it is an extremely brutal institution. Every student’s going to know that slavery is an exploitive institution, but the details of that exploitation I think are always worth talking about. Even before we talk about resistance, you’ve gotta make sure that students understand exactly the horrors of slavery.

First of all, there’s the slave trade, involuntarily bringing over people from Africa into America. They’re on these crowded ships, there’s a very famous image, it’s an image which comes from the way enslaved people are supposed to be stored on a ship. They’re basically in coffin-size containers, and they sleep that way, and they don’t move from those spots, and you traveled across the ocean in a spot like that. This is before modern sanitation is part of this, disease and death are part of this. These are terrible experiences, but what people don’t realize, is the image which everybody’s familiar with, and your students I’m sure in every textbook that you can find, they have this image, that image is the reformer’s image. That’s an image of how it’d be more humane to transport people across the ocean in these coffin-size spaces, not what actually happened.

People are vulnerable to rape, to death, on these passages. It’s the worst horror you can possibly imagine. Then, of course, slavery is the context in which racism develops. People don’t come with ideas about race until you actually see people degraded, and you see them as slaves, and that gets fully developed in the United States because of slavery. Another feature of slavery is that it’s perpetual. Once you’re in it, it’s for your life, and then, if you have children, it’s for the lives of your children, and they pass it on to their children. There’s basically no way out of the institution.

Another feature of slavery, which, again, this is on the horror side of slavery, is there’s no such thing as legal marriage in slavery. Because marriage is a claim that two people can make on each other, it often involves property claims, and masters don’t want to concede that there’s anybody who has a property claim on the human beings they own, other than the masters, and therefore they don’t allow people to be legally married. They can permit two people to live together and have a little ceremony, which they’ll abide by until they don’t want to abide by it, but there is no legal institution of marriage.

Throughout much of slavery it’s a crime to teach someone how to read who was an enslaved person, because reading is seen as the way in which people can learn about the rest of the world, and get ideas, which might undermine slavery. An enslaved person can be whipped at any time for various transgressions, or other kinds of punishments like that. There’s no crime of rape in slavery. If you’re a woman and you’re enslaved, and a white man sexually assaults you, you can’t go to the police, you can’t go to courts of any sort. That’s not a crime.

In fact, this is one of the great ironies of slavery, because if you’re a woman and you’re owned by a master, no matter who rapes you, the only legal recourse would be if your master thought there was a violation, and your master could bring the person who raped you to court on a charge of trespass. It’s trespassing, it’s his property, and someone else has trespassed on his property. But, if a master rapes you, and this happens all the time, it’s built into the institution, or anybody on the plantation who’s white, that’s not a crime. It’s not a crime if blacks rape you as well, so women are extremely vulnerable in slavery.

You don’t need a license to own anybody in slavery. There are crazy people, because there is no requirement, there are crazy people, there are sadists. A certain portion of the population are sadists who take pleasure in watching the pain of others, but even if you find some kind people who happen to be masters because you’re born into it basically, that master can die, that master can go bankrupt. You have to live your whole life with the uncertainty of into whose hands you might fall.

If you move, if the farm you’re on involves movement, this happens to whites, the big movement West is one of the great movements of American history. If you move—well, if you’re a free person, you move with your family. If you’re an enslaved person, unless your family happens to be on the plantation that also moves, and that is not as common as you might think, because usually families exist across plantations. When I say family, it’s not the legal marriage we’re talking about, but it is relationships of love which exist, and people have children and so forth. When your farm moves, you may be leaving behind large parts of the people you love.

So, that’s the one side of slavery, which is the tremendous brutality of slavery, and you can go on and on describing this to students. On the other hand, there’s another side of slavery, and this is the other part you have to keep in mind. What is that? Well, that is that within the institution of slavery, the people who were enslaved create a culture, which has become one of the most wonderful cultures on earth.

When you look around you, and you see the wonderful thing that African-Americans do in our society today, where does that all come from exactly? The culture that forges those wonderful institutions—the music, the religion, for example—all those things happen in the institution of slavery. Somehow in the midst of this exploitation, there is tremendous achievement that goes on at the same time. That’s the essence of resistance. There’s obviously the church, and this has always been a central part of African American life, extraordinary devotion to religion.

Some of the great African-American thinkers went through the church, Martin Luther King, or Malcolm X, the church is the place where African-Americans thrive. The family, now you might say as I said before, that the horror of slavery is there’s no legal marriage, but people fall in love. We know that they tried to do what they could to stay together. When slavery ended in 1865, one of the first things that people did who had once been enslaved was they searched for their relatives, they traveled, and they search for people who they loved.

This happened all over the South when slavery is over, and so one of the great stories of slavery is despite the fact that it’s structured so that families are destroyed, in fact families are not destroyed, they thrive, and people try to stay together with their families. The distinct forms of African-American music and dance come into existence in the institution of slavery. This is the place where the great rhetoric occurs. Where did Martin Luther King, where does that voice come from exactly? It comes from African-American culture, and that culture is formed in the institution of slavery.

You can see it when you read Frederick Douglass. Frederick Douglass is one of the great writers, he was also a great speaker, but we haven’t got his voice, but you can read Frederick Douglass, and you can hear an incredibly educated man who is also able to communicate extraordinarily. Then the abolitionist movement, the movement for freedom in the United States, of which African-Americans played a big role. It’s an interracial movement, but African-Americans play a huge role in that.

That movement, which has inspired us all, then it continues as the fight against racism continues after slavery. There’s the reconstruction period once slavery is ended, the brief period when African Americans are able to do things, provide for education and so forth, and get their families together. That is part of the great heritage that comes out of the institution of slavery. The civil rights movement, again, that’s one of the later fights during the 1960s. It’s the ending of segregation in America, the movement to end legal segregation, but the great story there is that has its roots in the institution of slavery.

The African-American community creates the tactics which will inspire all Americans as to the love of freedom. What did I just say? Two things happen in slavery: tremendous exploitation, and at the same time, a flowering of African-American culture. The two don’t quite mesh, but of course you can’t do one without the other. Those are central things you want students to recognize. I think the best way to approach this subject is first to talk about historians, what historians have said about this topic of resistance.

Now you might think, “Well, that’s a little bit of a diversion, right?” You really want to focus first on the African-American experience, listen to the voices of African-Americans who were resisting, but I think there’s something prior to that because historians in a sense determine how we view the past in a way. They’re read by other historians, they write the histories that people read. If you just read documents and you don’t have any framework, you’re simply lost, and you never learn anything.

One of the important things, I think, is to give students a sense that historians are important. Another point you can make, which is related, is that ... Now, this is a funny thing to say, but I think if you can get your students to realize this, this is important—that history changes over time. That’s a strange thing to say, that history changes over time, because you’d think that an event that happened in 1830 is dead and doesn’t change over time. What can someone possibly mean when you say history changes over time?

It means that when you bring modern eyes, and they’re constantly changing, the eyes of someone who was alive in 1950 is different from those alive in 1970, and different from today. As your eyes change, you can go back and look at a date in the past, you can look at an event in the past, and you can see different things. When you go to a library for example to study the subject, when you pick out any book during a certain period of time, the first question you ought to ask—your students ought to ask, is, “Well, when was this written? What is the dominant set of ideas that’s occurring during this period?”

That’s the framework I’d like to give you now, okay? What I want to talk about briefly is, beginning in the 20th century, what historians have said about slavery and how that shaped the framework, and then point out where the conversation is today in modern times. The first historian I’d like to look at is—a man who was extremely influential at the turn of the 20th century—is a man named Ulrich B. Phillips. He was a professor of history, and he wrote a series of books, but more than that he also had students.

This is the way professors get to be influential. Professors, the ones who award the Ph.Ds. to people, who go on to teach at other universities, and therefore his influence became widespread. If you go into a library today, for example, and pick out any book on slavery written before the 1950s, 9 times out of 10 you would discover that they were either written by Phillips, or by a Phillips student, so he was extremely influential. His basic interpretation of slavery was, as he says in one of his books, and this is a quote from him now he says, “A Negro was what a white man made him.”

Now remember Phillips is living at a time when we had the period of segregation in America. Racism among whites was extremely intense and severe, and Phillips is just in that tradition. He’s a white Southerner, and so all this writing he does about slavery comes from that perspective. He read all the sources, people recognize he’s a careful historian, and you can find a lot in the sources. It’s the same way you can read the Bible and find many different things in the Bible. Phillips found what he was looking for in these documents.

His basic assumption is masters were nice people, they were benevolent, slavery was a school where African-Americans are trained and civilized because he considered them uncivilized in Africa. African Americans he thought of as they were loyal to the masters, they were lazy, and basically they were under the control of the masters. One of the symptoms of that, was that there were very few slave rebellions. That there was, in terms of the topic of resistance, there wasn’t that much resistance to slavery, and in his mind the resistance he was looking for was slave rebellions.

This is a whole package, right? This is a vision of African-Americans as loyal to the masters, as masters being kind, and the fact that there were few slave rebellions. There were some dissenters at the time, and there’s a wonderful man named Carter G. Woodson who founded the Association For The Study of Negro History and Life in 1915. He was African-American, and a whole cadre of African-American historians were writing about slavery, and they were writing from a very different perspective.

We have Black history month, and he is the founder of Black history month basically at an earlier time. He was writing something different, and then there were a few other historians who also looked at the past and were writing something different as well. No, I mean, he creates an institution, and he creates a tradition, and there are writers who are in that tradition. There’s journals, the Journal of Negro History dates from that period. They were considered very credible by many African-Americans, but if you went to a white University, major American institutions, and you walked into their library, you would get Phillips, and those people who are with Carter G. Woodson wouldn’t be in those libraries basically.

That was the case during much of the era of segregation in the United States. That view of the past, the view of slavery, was shaped in a sense by people’s experience in the 20th century of segregation, and the racism of the 20th century. Then things began to change, so what happens is you begin to get the beginnings of the civil rights movement in the 1950s. The entire structure of laws, which created segregation in America, comes under attack. The most famous attack is in segregated schooling, where for much of this earlier period in the 20th century, it was legal to segregate the schools.

Then in 1954, in the famous Brown v. Board of Education case, the decision was made by the Supreme Court that if you separate the races, you can never give them an equal education, and therefore segregation was unconstitutional. That was just one of many, many decisions, but the great movement which extended into the 1960s and beyond, which attacked segregation, that changed the world. Remember when I said that history changes over time? History is going to change as well, because you can’t have the attack on segregation just sitting there alone.

People then go back, and they relook at slavery. They say, “The segregationist Ulrich B. Phillips, he wrote the history, but what if we looked at it again, but looked at it with different eyes? What if we tried to see the places where maybe there was more resistance, or maybe the nature of slavery was misunderstood?” Therefore, they go back. The key figure here is in 1956 a man named Kenneth Stampp wrote a book, and it was another interpretation of slavery, in which he attacked the interpretation of Ulrich B. Phillips.

The most famous section of that book is a chapter called, “To Make Them Stand in Fear.” He says slavery was not about the kindness of masters to enslave people, actually what slavery was about was whips and guns. The only reason why people became slaves was not because they loved their masters, it was because their masters had the control of force and kept them in slavery, and that’s what slavery was all about. It was not about kind and gentle relations between masters and slaves.

Once you go down the road of saying that slavery is about exploitation, it’s about brutality, it’s about force, it’s about whips and guns. Once you go down that road, then you begin to look at the issue of resistance differently as well because you wonder, “Okay, what about resistance?” You see, you can understand why there would be no resistance if you thought of slavery as benevolent, and masters as kind, but once you have the image of slavery as brutal, then you expect some additional resistance to pop up.

The world is changing, and the world of the 1950s is changing, and the 1960s is changing, and when they look at the period of slavery, they’re going to change their image of what that’s all about as well. Then what happened was, shortly after Stampp wrote, it was followed by another book, which was extremely influential in the 20th century. It set off huge conversations, and that was in 1959 by a historian named Stanley Elkins, and it was called, Slavery: A Problem in American Institutional and Intellectual Life.

He thought he was following in the footsteps of Stampp. Stampp said slavery was extremely brutal, and Elkins went along and said, “You know what? Not only was it brutal, it was one of the most brutal institutions that human beings have ever created.” He simply went down the road of brutality, and extended it, and he actually drew an analogy, an interesting analogy between the concentration camp, which the world had just experienced during that period, the concentration camp designed to exterminate Jews in Europe by the Nazis, and they had images from there when those camps were liberated, and the terrible atrocities that’s went on there.

He said that slavery was like that, it was as brutal as that. Therefore, he said, what happens is it has a tremendous psychological toll, it has a tremendous psychological effect, which is destructive to the people who experience it. In fact, there was evidence that that was the case in the Nazi concentration camps, and he said if you go back and look at slavery, what you discover is, yeah, they’re not revolting, because they’re ... He used the phrase infantilized, they become childlike. They have psychological defenses against this kind of brutality, and he said, “It happened to Jews as well, in Nazi Germany, that you identify with the master and so forth.”

Now this is chilling actually, when you go back and you read this. It’s quite unbelievable, you see, because on the one hand I was describing a moment in time when the dominance of Ulrich B. Phillips, who described slavery as this benevolent institution, that dominance was being challenged, it’s about to be overthrown. Yet what Elkins does is he says that slavery, oh, it’s brutal. He goes down the road that Stampp went down, but he goes further, and he says it’s so brutal that it destroys the people who were enslaved. It destroys their independence and character, and therefore, the odd thing about the Elkins interpretation is they came at the subject of slavery from completely different perspectives.

Phillips on the one hand, Elkins on the other hand—completely different perspectives. Phillips saying it’s a benevolent, kind institution, Elkins saying it’s the most brutal institution, but their conclusion about resistance was chillingly the same. Elkins said there wasn’t much resistance because the culture was so completely destroyed.

So, in a way, you see, given that I’ve said that the thing about slavery is it’s got these two sides, right? It’s got the brutality side, and you can see that Stampp and Elkins are going down the brutality side of things, and then it also has this survival of African-American culture, and this amazing results of cultural flourishing, which also goes on in slavery and after slavery is over. What’s happening is when Elkins writes, he’s wiped out the second part. He’s rejecting the idea of benevolent masters, but he’s saying is it was so brutal that it destroyed African-American culture and society.

Hasan Kwame Jeffries: You’re listening to Kenneth Greenberg as he talks about slave resistance in this episode of Teaching Hard History: American Slavery. I’m your host Hasan Kwame Jeffries. This podcast is a companion to the Southern Poverty Law Center’s reportwood on teaching slavery in American schools. You can find the report at LearningForJustice.org/HardHistory. Now back to Kenneth Greenberg.

Kenneth Greenberg: All these historians writing in an earlier time generally defined resistance as slave rebellions. That’s the iconic moment of resistance, when someone rises up with a gun, or an ax, or a sword, and kills the master. That’s an act of resistance which is violent, and that can lead to slave rebellions if you get other people to do it as well. That’s the iconic moment of resistance. What happened was, as people after Stampp, and even before Stampp, began to talk about resistance, they said there were more rebellions than people had thought about, and they identified many rebellions which got repressed.

Masters didn’t want to talk about rebellions, didn’t want to write about rebellions, that information was repressed. Once you’re a historian who realizes, who was on the lookout for more rebellious activity, you discover that there is more rebellious activity. On the other hand, if you put rebellions in a comparative context, in other words, not just looking at them in the United States, but say you compare rebellions in other slave societies to rebellions in the United States, every historian who looks at this says, “The American rebellions are smaller in number, and they seem to be smaller in size.”

To take one example, one of the most famous slave rebellions, is the Nat Turner rebellion in Virginia in 1831. That involves maybe 60 rebels who kill 55 white people, and you compare that to Haiti, which is inspired by the French Revolution, where the entire country undergoes a revolution. Thousands and thousands of whites are slaughtered in this revolution, and Haiti becomes the first country ruled by Africans in the New World. Russian surf rebellions, Russian serfdom is very much like slavery, and there are hundreds of thousands of people involved in those rebellions.

Brazil is full of these gigantic rebellions of tens of thousands, hundreds of thousands of people, or Caribbean rebellions and so forth. You go back to the Nat Turner rebellion, one of the biggest—not the biggest—but one of the biggest American rebellions, and it involves 60. You get back to this question of, well, where is the resistance exactly? Well first there was this huge outpouring saying, “Well the absence of rebellions doesn’t mean that there wasn’t resistance, it means that resistance took other forms.”

For example, in the United States, the United states had a much larger white population than many of these other areas, and it was hard to have a rebellion in an area where there were so many whites who could organize and repress the rebellion right away. The whites in the United States were organized in powerful militias at the state level, and at the local level, and they could just jump in and repress rebellion. Plantation sizes were much smaller, so the units were smaller.

The terrain is inhospitable to rebellions, the places where you get lots of rebellions. You can hide in the mountains, you can hide in the swamps, and the United States had comparatively fewer of those areas. Therefore, the feeling is, well, there are fewer big rebellions in the United States, but that has nothing to do about resistance to slavery. Resistance to slavery in the United States took other forms. Of all the things that you want to be able to teach students, it’s this: it’s the changing definition of resistance, which does the most to change our opinion of what resistance to slavery is all about.

As long as you focus on rebellions, all those historians who were of that era, they were looking for rebellions. Only when you change the definition of what resistance is do you begin to get a different picture of what slavery is all about. If you want to engage in rebellion, and rebellion meaning “rise up and kill the masters,” if you weren’t going to do that, how could you resist slavery? Now let me give you examples, okay? You can ask your students to come up with these examples.

One thing is you could light a town on fire. It doesn’t take much. You’re a lone person, you hate your master, and you simply light up a portion of the town, and the whole town burns, or the plantation house burns. Again, no one’s writing about there’s just been a tremendous slave rebellion there, on the other hand it can be very destructive. Southern cities burned all the time, and we don’t know why they burned, but I can tell you that they burned in part because of resistance to slavery.

As an individual you could put ground glass—if you’re a cook—you can put ground glass in your master’s oatmeal. People can be very creative about the ways in which they resisted institution. You don’t need to rise up. If you rise up with swords and axes and hatchets, you die, but if you put ground glass in your master’s oatmeal, your master will die.

Another way to resist, is you can slow the pace of work. What masters thought they were seeing was a lazy group of slaves in the institution of slavery, but actually what they were looking at were people who were resisting by slowing the pace of work. Why would you work at a fast pace if you were an enslaved person? You could break tools, the wagon. Masters were always talking about this, “My tools, somehow, they break all the time,” and of course enslaved people don’t have an interest in making sure that these things work properly, and that’s another kind of resistance. You could also resist by feigning illness, you could say, “I’m sick today, I can’t work.” Now masters, of course, tried to fight that, and they had all kinds of techniques, but nonetheless that certainly happened enough.

You could engage in thievery at night when the plantation, the masters, were asleep, the whites were all asleep on the plantation, you could quietly break in and steal something if you wanted food for example. Another kind of resistance is you could learn to read. Remember there were those laws that said you weren’t allowed to read in the institution of slavery, and you were an enslaved person, you knew that this is something that the masters used to keep you under control, and therefore learning to read, figuring out the ways in which you could learn to read, would be another form of resistance.

Of course, if you could learn to read and to write, then one way they had of keeping you on the plantation was masters needed to write a pass. If you wanted to leave the plantation, the master would have to write a pass saying you were authorized to leave, where if you could write the pass yourself, well, that undermines a significant portion.

You could practice your own religion. Now I mentioned religion already, but, you see, masters wanted enslaved people to have religion, but the religion that masters had in mind was the religion in which you looked at the Bible, and you got messages about how God wanted you to obey your earthly masters. That’s the religion, and so masters tried to control what slaves learned about religion as much as possible. We know that didn’t happen. It didn’t work that way. Slaves created their own religious forms, had their own religious services, and hush harbors outside the existing churches. It’s called the invisible church that was created, and that’s the church which ultimately is going to inspire people like Malcolm X become part of that tradition, and Martin Luther King as well.

Marriage and family—again, the master will, at his indulgence, might let you have a relationship, but if you have those relationships on your own, fall in love on your own, that’s another way of resisting. Running away—slavery is not a prison, there are no walls around plantations. Every night, when the master goes to sleep, there are no armed guards guarding the plantation. You can walk away from that plantation. Now there are consequences. The whole society is keyed to catch you and so forth, but nonetheless, at night you can go into the woods, you can meet your friends, you can meet the people you love.

Slavery is full of those kinds of meetings, so what I’m describing here is this recognition. You see how what I’m talking about is the movement away from thinking resistance to slavery is all about slave rebellions. I’m telling you that resistance to slavery is all about religion, learning to read, running away. Those are the acts of resistance which people engaged in all the time. It’s not that these were rare, these were daily occurrences in slavery. If you were an enslaved person, you had millions of ways of resisting your masters.

This also led to—ultimately, as historians write about this—to a role for women in resistance. You see, if you defined resistance only as slave rebellion, we know that, for a variety of reasons, slave rebellions is mostly a male enslaved person’s activity. There are some women who get involved, and they’re interesting stories, but the typical slave rebellion involves men, and therefore women are left out of the issue of resistance. Modern historians today, following in the tradition of redefining resistance, have said, “There’s an amazing thing.” One wonderful historian, Stephanie Camp, who describes parties, what I’ve just been describing, where you leave your own plantation and you go to someone else’s house, and you party together at night. They’re illegal parties, and masters tried to stop these all the time, and Stephanie Camp is a historian who says, “Well this is another form of resistance.”

Also, sexual exploitation—remember, it’s built into the institution of slavery. It is at the heart of slavery in many ways, and women resisted those in a million ways. They resisted by force, but they resisted in many other ways as well. The other thing about resistance to keep in mind is that the consequences of resistance were huge. In fact, the way to think about slavery ending is that the resistance of people who were enslaved helps bring about maybe the central cause of the end of slavery.

Now, this is an important point. It’s the easiest thing in the world for students to say something like— well, if you ask a student, “How did slavery end?” They know about the Emancipation Proclamation, or they knew about the constitutional amendments, and they talk about Abraham Lincoln ended slavery. That would be reconfirming that African-Americans had nothing to do with their own liberation.

We now know that’s not the case. It’s these acts of resistance which create circumstances which lead to the collapse of slavery. I’ll just give you a few examples of this, but this is really important—running away. Now at first you think, well what’s running away? You leave your plantation at night, and often you’d go back during the day, okay? That doesn’t seem like it’s going to bring slavery to an end. But what if you run away to the North? There are some number of people, there are thousands, tens of thousands, of enslaved people who run away to the north.

The North does not have slavery at least by this period of time—they had it earlier. You could run away to the North, and then the United States Constitution says that states have an obligation to return runaway slaves, because the slave states wouldn’t join the union unless they were sure that once enslaved people ran away to a so-called free state, that they had to be returned. There are laws passed at the federal level to ensure that an escaped enslaved person who is found in the North is brought back into the South.

The act of running away under those circumstances means that the North is implicated in slavery. You can go to a place like Boston. You could leave Virginia as an enslaved person, you could find your way to Boston, and seek friends in Boston. Again, you wouldn’t be free, right? You’d be protected by people, if they caught you, you could be sent back, at least till just before the Civil War. The question is, what’s gonna happen? Well, you’re going to get arrested if they find you.

Your master will try to find you in the North, and therefore you could be in Boston, which thinks of itself as a part of a free state, and you discover you’re not really free of slavery. Some Northerners, who otherwise might not get excited about slavery, say, “Well this is Southerners extending slavery into the North,” and there were people who will violently defend the freedom of enslaved people. That’s how— think of what I just said—the act of running away, done on the scale of moving from South to North, creates circumstances, which leads to conflict between North and South.

Of course, that’s going to lead to the Civil War, ultimately, and lead to the end of slavery. Even during the Civil War itself, think about this, at first when Northern armies are fighting Southern armies, one of the goals of the war is not to end slavery. In fact, when Lincoln is inaugurated, he doesn’t want to have the South succeed, he doesn’t want to end slavery at that time at least. In his inauguration he says, “I’m not going to abolish slavery,” in fact it would have been told as probably unconstitutional at that point, but he says, “I’m not going to abolish slavery, that’s not my goal.”

He’s interested in the extension of slavery in the territories, which is another subject here. Lincoln doesn’t want that, so at the beginning of the Civil War, it’s not a war to end slavery, but if you’re an African-American, and the Northern soldiers go past you, what are you then? Are you a slave at that point, or are you free? If you’re still in Virginia, and the Northern armies extend—or in Louisiana, or Mississippi—and the Northern armies have conquered that area and occupied that area, who are the people who are in that area?

They still have slavery, they’re still legally slaves, so the question is, what are the armies going to do? What is the President going to do about this kind of a situation? Are the Northern armies going to arrest an enslaved person who finds himself behind union lines, or runs away from a Southern plantation? Are they going to arrest that person, and force him back to his master? Who initiates the end of slavery under those circumstances? It’s the person who runs away, who creates circumstances, which make it impossible for slavery to survive.

If you want to look at the way slavery ends, it’s this kind of resistance, not slave rebellion. The simple act of running away, and there are many other acts like this basically, which create circumstances which are going to strain slavery, and lead ultimately to the end of slavery.

Hasan Kwame Jeffries: This is Teaching Hard History: American Slavery, and I’m your host Hasan Kwame Jeffries. Along with this podcast, you can find a detailed framework for teaching slavery along with sample units and primary sources at LearningForJustice.org/HardHistory. Again, here’s Kenneth Greenberg.

Kenneth Greenberg: I’d like to end by saying a few words about how to teach this to students because it’s important that a teacher have these concepts in mind and know where they’re going with the teaching, but you’ll also want material that students can read, and appreciate things for themselves. My general advice is don’t read historians, that creates too much of a distance with students. They need to read the original documents, and my recommendation is that they read the words of African-Americans.

If you want to learn about resistance, that’s the place to go, so I have three recommendations, and what you can do is take excerpts from these books generally. They’re mostly too big for students to read in their entirety, but if you show them excerpts, it can reveal a great deal. The first suggestion I have is that there’s an amazing document called, The Confessions of Nat Turner. This refers back to the rebellion of 1831, and I’ve actually edited those confessions.

They’re only about 20 pages or so, but I’ve edited them with some other documents of the period. Trial records of the rebels, newspaper accounts, a document written by a Northerner from Boston, who is talking about the need to use violence to end slavery, an African-American man named David Walker.

A diary from the governor of Virginia, and then someone writing a summary of the debate in the Virginia legislature. They were so frightened in Virginia by the Nat Turner rebellion, that they actually considered abolishing slavery as a result.

They didn’t, but that was an interesting thing, so I recommend that you pick excerpts from a few of those documents, and in particular, The Confessions of Nat Turner. This is a slightly side thing, but this is an interesting thing, when you read, The Confessions of Nat Turner, and you see all the documents of the period, the one thing you need to emphasize with students I would say, of all others, is that they need to pay attention as to whose voice they are hearing. Now you might say, “Well what exactly is, The Confessions of Nat Turner?”

Well, let me tell you how it got made. Nat Turner escaped capture for two months after the rebellion. He hid out in the woods. Finally, when he was captured, it was two months after the rebellion. He was brought to his jail cell, and there were about 10 days or so between when he was captured, and when he was tried and hanged 10 days later. While he was in his jail cell, he had a white visitor, a lawyer—not his lawyer—but a white visitor named Thomas Gray. Thomas Gray met Nat Turner in his jail cell and wanted to find out the real story of the rebellion and basically interviewed him.

What The Confessions of Nat Turner, are, are the result of those interviews. If you read it, it sounds like it’s Nat Turner’s voice, except there are some places where Gray intentionally says, “Well, here’s the situation.” He’s using his voice basically, but most of it is written as if it’s Nat Turner’s voice. One question you have to ask students is “How do you know it’s Nat Turner’s voice?” Nat Turner doesn’t actually write this down. There is no tape recorder, right? It’s Thomas Gray who writes everything down, organizes the confessions, so one of the great puzzles of doing any document from the past like this is to ask the question of whose voice do you hear?

Let me just read you a section of this. It’s worth thinking about. This is from the beginning of the confessions. I’ll read you this because it can be used to illustrate a couple of things—the issue of voice, but other things as well. This is Nat Turner describing his childhood, and he says the following, “In my childhood, a circumstance occurred, which made an indelible impression on my mind, and laid the groundwork of that enthusiasm, which has terminated so fatally to many, both white and black, and for which I’m about to atone at the gallows.”

In other words, this is in Nat Turner’s voice, right? Well when I read this, and again, your students won’t pick this up right away, I think that you have to point this out to them. Have them linger over this. Did Nat Turner really say this? Did he refer to the fact that he’s about to atone at the gallows? Everything I know about Nat Turner, and if they read some more about this, will discover that he’s a man thinking that he was sent by God to end slavery. For him to say that he refers to this enthusiasm, meaning (a religious enthusiasm was a negative term basically) he calls himself a fanatic there basically, and it ended up killing so many people, black and white, and he’s about to atone at the gallows. I know Nat Turner didn’t say that.

So, one of the lessons you want to teach your students is they need to be, not only when they read works of history, as to who the historian is, and when they wrote, but when they read a primary source as well, they need to know who wrote it. Actually, if they read anywhere, all these other documents which are included in the volume on The Confessions of Nat Turner—newspaper accounts, trial records—those aren’t unmediated African-American voices.

What’s a trial record? We have a few sentences that purport to be African-American voices, but if you’re an African-American captured under these circumstances, and you’re testifying at a trial, are you speaking freely of what’s on your mind? My guess is not, so, again it’s important to teach students how to read a source like this and to be skeptical about something like this.

Then there are places where you definitely hear Nat Turner’s voice, and here’s one, and this gets at the religious angle of things, too, how important religion is. Listen to what he says here. He’s describing his religious visions, he thinks that God has chosen him to free his people from enslavement. He thinks of himself as a prophet, kind of like Moses. This is Nat Turner purportedly speaking. “As I was praying one day at my plow, the Spirit spoke to me saying,”—and here’s a quote, he’s quoting the Spirit, “Seek ye the kingdom of heaven, and all things shall be added unto you.” Then Gray inserts his voice, and he says, “What do you mean by the Spirit?”

Then Nat Turner answers, “The Spirit that spoke to the prophets in former days, and I was greatly astonished, and for two years prayed continuously when my duty would permit. Then I had the same revelation again,” so when you get these revelations, this is Nat Turner’s voice, and you can see the power of the religion. Nat Turner has the strength to undertake this because of his religion, it’s part of the larger way of attacking slavery. There’s another moment too in the confessions, and this is probably ... If you want to read, if you want to go over one thing with your students, it’s this extraordinary moment in the volume I edited, it’s on page 46.

Gray is talking to Turner, who’s describing the rebellion, and Gray says, “Do you not find yourself mistaken now?” See, Gray wants to be reassured too, he’s hoping that Nat Turner’s going to say, “You know, this was a stupid idea, everybody got killed, I’m about to get killed.” That’s what he wants Turner to say, okay? Here’s what Turner does say, and this is where I hear his voice, and see if your students hear the same voice. When Gray says, “Do you not find yourself mistaken now?” Nat Turner answers, “Was not Christ crucified?” Was not Christ crucified?

It just sends chills up and down your spine. Here’s a guy who knows he’s going to be killed, who’s surrounded by his enemies, who has no chance of survival, and he has the tremendous confidence to speak back to Gray in that jail cell, and says—compare himself to Christ, saying, “Christ was crucified. You could lose, you could die, and still be on the right side of things.” It’s an extraordinary moment, and again, it’s the power of religion in here mixed in.

Now, it’s a rebellion, that’s certainly the case, right? The other thing about the confessions is you get to see, he talks about his family, the influence of his parents telling him he’s a special person. He talks about learning to read. Again, these are other forms of resistance, which lead up to the rebellion. He runs away at one point. He uses running away as a tactic. The rebellion begins because he gathers with a few friends, and they have a roast pig in the woods, and they all bring various things to a party in the woods, and that’s how the rebellion begins.

You see how when you say it’s a rebellion, it’s true, but it has all the elements of things which I’ve been describing as a rebellious activity leading up to it as well. Another book that I recommend you read with your students is a book by Harriet Jacobs. It’s called, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. This is an amazing book because most people who ran away from slavery were men. When you run away from slavery and then you write your life story, what typically happens is you run to the North when you’ve learned to read somehow, then you write your story, or you tell it to somebody else who writes it down for you, but that’s the story.

Most people who did that, who wrote their stories, who escaped from slavery that way, were men. Women tended not want to leave their family behind, they sometimes had children they refused to leave as well, so it was men who tended to do it much more. This, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, is one of the few books written by a woman where you can see what resistance to slavery is all about from the perspective of a woman. I want to give you a sense of a woman in slavery, and how vulnerable they were to attack within the institution of slavery.

Here’s a section. It’s on page—in the volume I’m using, it’s on page 470. It says the following—she’s describing being vulnerable, sexually vulnerable to her master. This is tricky because this is 19th-century language, right? She’s not gonna get too explicit here, but you know what she’s talking about. She says, “He tried his utmost,” (the master) “tried his utmost to corrupt the pure principles my grandmother had instilled.” Again, she had a very powerful grandmother, a free black woman actually who taught her morality basically.

“He,” meaning the master, “peopled my young mind with unclean images, such as only a vile monster could think of. I turned from him with disgust and hatred, but he was my master. I was compelled to live under the same roof with him, where I saw a man 40 years my senior daily violating the most sacred commandments of nature. He told me I was his property, that I must be subject to his will in all things. My soul revolted against the mean tyranny, but where could I turn for protection? No matter whether the slave girl be as black as ebony, or as fair as her mistress, in either case there is no shadow of law to protect her from insult, from violence, or even from death. All these are inflicted by fiends who bear the shape of men.”

This book describes a woman who is vulnerable to sexual exploitation, and she also describes her ways of resisting. Now the ways are amazing. She goes to her grandmother—her grandmother’s a free person. She tries to get another white man who’s in the neighborhood. She has an affair with that man, which she believes she chooses voluntarily—that’s not so clear whether it’s voluntary—and he’s powerful, and she hopes to use his power against the master. She’ll resist physically by force. So, she has a million ways of resisting.

As she describes it, she successfully resists rape by her master, but some historians have looked at that and they said, “She just doesn’t want to write about this,” because she’s writing for an audience of Northern middle-class white women who don’t want to hear about a woman getting raped and expected her to choose death rather than submit to rape. Nonetheless, it’s a complicated story, but it’s a story of a woman, and the vulnerability of a woman in the institution of slavery, and the way she resists.

She does not, in the end, resist by creating a rebellion. Unlike Nat Turner, she does resist by running away, ultimately, in the end. Before she runs away, she actually hides in her attic for seven years. I know this sounds incredible, but her grandmother’s attic—her grandmother had an attic. She could look out the window and watch her children grow up. She never revealed herself to them, but to get away from the master, she chose that. Before she ran away, she actually did that. Many people read this, and they said, “It couldn’t happen. That sounds like a crazy story.” There’s a wonderful historian who has gone over this, and she’s confirmed virtually everything that Harriet Jacobs said about this experience.

The last person I want to talk about is Frederick Douglass, who wrote his narrative of his experience in slavery called, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass. It got published in the North, and one of the key moments in that document is something where he’s describing being an enslaved person and the ways in which he resists.

One big way is he learns to read, and he understands reading as resistance. At first, he has a kind mistress who starts to teach him to read. The master says, “This is going to undermine slavery.” He stops the mistress from doing this, and so Douglass is a resilient man and discovers a way to learn to read without the mistress. He actually—whatever money he can collect, or objects he has, he gets poor white kids, he gives them things, and they teach him the alphabet, and teach him how to read basically, but he does this himself, and understands reading as an act of resistance.

There’s another amazing moment, too. He is sent at one point—because he resists slavery—he is sent at one point to someone known as a slave breaker. It’s a really tough guy, his master wasn’t tough enough, and so this is someone who will brutalize him and treat him so poorly that they’re hoping to break the spirit of Frederick Douglass, but Douglass is not so easily broken. This man’s name is Mr. Covey, and at one point in his narrative, Douglass describes the confrontation. He decides he can’t take this anymore, he’s just beaten over and over again, the demands on him are irrational excuses for beating him, and so he decides he’s going to stand up to Covey.

Now in his mind, he’s gonna lose his life. This is almost like a rebellion, okay? He stands up to Covey, and when Covey starts to beat him, he beats Covey back. The two of them fight each other for a long period of time, probably for hours, and they’re hitting each other back and forth, and back and forth, and back and forth. We don’t know what was in Covey’s mind during this whole time. He tries to get other enslaved people to join him to try to subdue Douglas, but they won’t do it. They said, “We’re not here to do that kind of work for you.”

So, this is, basically, from Douglass’s point of view, it’s a draw. He stands up, and then his experience is Covey no longer beats him after that. In other words, he has resisted slavery—no longer beats him. The way Douglass describes the feeling of having stood up to Covey is he says, “From that day forward, I no longer felt I was a slave.” Even though legally he was a slave, even though he was in slavery, Covey himself understood what his limits were and couldn’t subdue Frederick Douglass.

Douglass didn’t even have to flee to the North to get the sense that he was liberated somehow, that this act of resisting, this willingness to die basically, to stand up as an individual. Not a slave rebellion, not the Nat Turner rebellion, but just standing up gives him the sense of freedom. The other moment is when he runs away, but actually the key moment in the Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass is the moment when he stands up to Covey, and he gets this inner sense of his own worth and freedom.

Those are examples that you can teach with students about the acts of resistance, of which enslaved people were capable of. It’s an amazing story, and you have an obligation to inspire your students with these acts of resistance. They inspire me, they should inspire you, and they should inspire your students.

Hasan Kwame Jeffries: Kenneth S. Greenberg is a distinguished professor of history at Suffolk University. He is also the author of, Honor and Slavery, and the editor of Nat Turner: And Related Documents. Before we wrap things up, I wanted you to hear from another educator who’s starting to expand her slavery curriculum with her students, so once again, here’s librarian Izzy Anderson who teaches middle school in the Arkansas Delta.

Izzy Anderson: I have nine boys and one girl in this class. I was going to do a quick overview of black history, but I realized that my kids don’t really know anything about slavery, and they also don’t have a concept of a timeline. They don’t understand the distance between Martin Luther King and slavery, or how long slavery had been around. They just didn’t know anything about it, so I was, “Oh, we have to stop here,” because slavery is understanding the black experience, and their experience in the world as black people that live in the deep South.

Black people whose grandparents, and great-great-grandparents didn’t leave during the great migration after slavery. They’re the ancestors of the people who stayed here, and so I was like, I feel like they really need to understand slavery and that experience in order to understand where they came from. I’m like, “Okay, I’m not the person that should be teaching them about where they came from. I’m not the person who should be teaching them about this trauma, but I’m the only person that’s here who’s going to do it, so I have to figure out how to do it right.”

My concern was that they were just going to be like, “This is horrible, and it makes me feel really bad, and I feel really bad about this,” because obviously conversations about slavery, and being like, “Your ancestors were slaves, your ancestors were abused and murdered for a really long time, and mine weren’t.” It’s a really hard conversation to have, and I was really worried, okay if I’m gonna lay this out on the table for them, am I going to traumatize them? Am I going to give them all this horrible information, and they’re going to hear about all this horrible stuff, and all this rape and stuff as sixth-graders, and then they’re just going to have nightmares, and it’s going to be horrible, and I’m going to get angry calls from parents, because their kids can’t sleep?

Should I whitewash it a little bit? Should I sanitize it a little bit for them, because they’re young, but still have the knowledge that nobody else may ever teach them about this again, and that sanitized version of it may be all that they learn about it? Should I just put it out on the table, and assume, or hope that it’s something that they can cope with? I feel like I need to talk to somebody who actually knows about this, and so that’s where I ended up finding this podcast, and then reaching out, and that really gave me a direction to go in.

I’m going to focus on resistance movements. I’m going to focus on the development of culture in the face of people who really didn’t want slaves to develop culture. Not to avoid those really, really tough topics— that our kids are exposed to violence and things in their real lives, and in media all the time. For us to assume that they can’t handle it is probably not giving them enough credit, and that I can tell them about these things as long as I frame it in the context of resistance, in the context of survival, of being like, “Okay, yes, black people endured this, but they also survived it, and thrived, and created a culture, and resisted all the time.”

If I teach it to them, all these things to them, in that context, then it’s going to be really powerful for them. That’s the direction that I’ve taken it. Once I really dove in and started to have these really scary conversations with kids, and telling them about these really scary things, they handled it much better than I thought that they were going to. They expressed that they were really happy to know this, and they took out of it what I had hoped that they could take out of it, which is this anger, but it’s a righteous anger.

I think looking at the people who change the world, there are often people that have righteous anger. I think if I can engender that, or help kids develop that anger, because there’s a lot of things now that they should be angry about. If that anger can be formed in a base of history and understanding of the world, then I hope that kids can go out, and my kids can go out and be advocates. That anger that I see in them is the right kind of anger, it’s what I wanted, and it’s what I want to continue to develop as I keep talking to them about these things.

I understand wanting to skirt around really tough topics, especially if your kids are younger, but just in general, those conversations can be really, really hard to have. You can be worried that you’re going to do something wrong, but I try to operate under the assumption that I have no idea whose classroom my kids are going to be going into in the future. What kind of person’s classroom, what they’re gonna teach them, whether or not what they’re gonna teach them is true.

We know history books leave huge chunks of things out, or make slavery seem fun, or make the Trail of Tears look like people were just happily migrating, because the white people asked them to, or whatever. I don’t know whether or not people are going to teach that, and I think for our kids to be informed citizens of the world, for our kids to understand and go out into the world, and be the advocates that we so desperately need, that we have to dive in. We have to teach them, because they have to know.

Even if it’s scary, I think just seeking out resources, and making sure that we’re asking the right questions of our fellow educators, and looking for the right resources, that it’ll be okay, because somebody’s got to do it, and it’s gonna have to be you, because you never know if it’s gonna be anybody else.

Hasan Kwame Jeffries: Teaching Hard History is a podcast from Learning for Justice, with special thanks to the University of Wisconsin Press. They’re the publishers of a valuable collection of essays called, Understanding and Teaching American Slavery. In each episode, we’re featuring a different scholar to talk about material from a chapter they authored in that collection. We’ve also adapted their recommendations into a set of teaching materials, which are available at LearningForJustice.org.

These materials include over 100 primary sources, sample units, and a detailed framework for teaching about the history of American slavery. Learning for Justice is a project of the Southern Poverty Law Center, providing free resources to educators who work with children from kindergarten through high school. You can also find those online at LearningForJustice.org. Thanks to Dr. Greenberg for sharing his insights with us.

This podcast was produced by Shea Shackleford, with production assistance from Tori Marlan, and Chris Dwyer at Suffolk University. Our theme song is “Kerr’s Negro Jig” by the Carolina Chocolate Drops, who graciously let us use it for this series. Additional music is by Chris Zabriskie. If you like what we’re doing, please let your friends and colleagues know, and take a minute to review us on iTunes. I’m Dr. Hasan Kwame Jeffries, Associate Professor of History at the Ohio State University, and your host. You’ve been listening to Teaching Hard History: American Slavery.

References

- Teaching Hard History: Text Library, Frederick Douglass Describes Enslavers

- The New York Times, The Historian Behind Slavery Apologists Like Kanye West (Ulrich B. Phillips)

- SPLC report, U.S. Education on American Slavery Sorely Lacking

- Association for the Study of African American Life, Founders of Black History Month: Carter G. Woodson

- Learning for Justice, Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas

- Kenneth M. Stampp, Peculiar institution: Slavery in the Ante-Bellum South

- Stanley Elkins, Slavery: A Problem in American Institutional and Intellectual Life

- Learning for Justice: Lesson, Nat Turner

- Kenneth S Greenberg (editor), The Confessions of Nat Turner: And Related Documents

- History News Network, Stephanie M. H. Camp

- Frederick Douglass, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave

- Learning for Justice, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl