Editor's Note: Please note that events may have changed since this story was written.

Editor's Note: Please note that events may have changed since this story was written.

The empty space left by the death of a young person seems somehow larger—perhaps because we sense not only the absence of who he was, but also of who he could have become. This emptiness can engulf an entire community, even a nation, when the death is unjust.

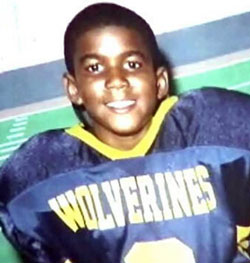

On Feb. 26, Trayvon Martin, a 17-year-old African-American high school student, was fatally shot on his way home from the convenience store. He carried a package of Skittles and an iced tea. He had no weapons. His killer, George Zimmerman (a neighborhood watch member more than 100 pounds heavier than Trayvon and armed with a semi-automatic pistol) still has not been arrested because he claims he shot Trayvon in self-defense.

Evidence of misconduct has clouded the case: an officer told a witness her story was incorrect. Police did not test Zimmerman for drugs or alcohol when they arrived on the scene. Tapes of a 911 operator telling Zimmerman not to pursue Trayvon were withheld from the public.

We must ask ourselves—Why would police take the word of a man holding a pistol over the body of a boy? Why would a witness’ story be changed? Why is 13-year-old Austin, an African-American neighbor, afraid he will be stereotyped by neighborhood watch members and police just as Martin was?

Some of these questions will be answered by investigators. Other questions—the deeper, more disturbing ones that ask about equality and intolerance—must be answered within our classrooms and our courtrooms. These dark questions have grown from our living rooms and our televisions. Their very existence attests that we, as a nation, are failing our Trayvon Martins.

A recent study by the Office for Civil Rights shows that the percentage of young black men suspended from school (as Martin was) is far greater than that of their peers. Another study, by The Sentencing Project, examines vastly disproportionate rates of incarceration for African-American men. We should be asking ourselves why these disparities exist.

Trayvon Martin was not a victim of Zimmerman alone. He was a victim of the lopsided school system that suspended him. He was a victim of a police force that assumes first that young black men are guilty. He was a victim of legislation, like Florida’s Stand Your Ground law, that gives citizens the unfettered right to kill if they feel threatened in any way.

Tomorrow, look around your classroom. Do you have any Trayvon Martins? As an educator, you have the power to stave off the emptiness of Trayvon’s death. Talk to your students about racism. Question legislation that endorses vigilantism. Speak up against police inaction. Champion your students’ rights.

Nothing will fully fill the void Zimmerman created in the lives of Trayvon’s family, friends and teachers. But Trayvon’s empty desk can become a symbol of awareness and change—a sign to our society that the current state of affairs is not acceptable.

Pettway is associate editor for Teaching Tolerance.