The Three B's are found posted on almost every wall at Blossomwood Elementary School in Huntsville, Alabama.

Be Respectful

Be Responsible

Be Resourceful

The Three B's are part of Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS), a systems-based method for improving student behavior, aspects of which are being implemented at Blossomwood.

"For us, it is about consistency," said Carol Costello, Blossomwood's assistant principal. "We needed to set schoolwide expectations for student behavior. PBIS gives our students, teachers, and staff a common language for discussing students' actions."

Less than three miles away, the same words adorn the 80-year-old walls of Lincoln Elementary, another school implementing PBIS. In some ways, Lincoln is similar to Blossomwood. Both schools score well on state testing, consistently meet the Adequate Yearly Progress requirements of No Child Left Behind, and have top-end attendance rates. Demographically, however, the schools are different. About 80 percent of Lincoln Elementary students receive a free or reduced-price lunch, while about 15 percent of Blossomwood students do. Lincoln's student body is 70 percent African American and 30 percent white, while Blossomwood's student body is 81 percent white and 18 percent African American.

Melinda Clark, Lincoln's curriculum specialist, likes PBIS because it is proactive. "We are addressing issues with student behavior before they happen," she said.

Lincoln and Blossomwood are among more than 7,000 schools nationwide implementing PBIS. The program was developed at the University of Oregon and has been shown to work at all grade levels and be effective in districts with greater concentrations of poverty and higher percentages of "at-risk" students. For those schools that effectively implement PBIS, the list of demonstrated rewards is long:

- reduced office referral rates of up to 50 percent per year;

- improved attendance and school engagement;

- improved academic achievement;

- reduced dropout rates;

- reduced delinquency in later years;

- improved school atmosphere; and

- reduced referrals to special education.

The need for PBIS is self-evident. Out-of-school suspension numbers outpace enrollment; juvenile judges find their courtrooms clogged by students, particularly students of color, who have been referred for non-violent misbehavior; and research has shown that school exclusion is ineffective at improving student behavior and may, in fact, be counterproductive. Research has also tied school exclusion to grade retention and dropout problems. The result? Too many students leave school, one way or another, because of school discipline.

Discipline issues also affect teacher attrition. Researchers estimate that almost half of new teachers are no longer in the profession by their fifth year. In a 2005 national survey of teachers leaving the profession, 44 percent of teachers, and 39 percent of highly qualified teachers, cited student behavior as a reason for leaving.

At a time when both students and teachers are leaving our schools because of discipline, a number of districts have been looking to try something different. PBIS — which requires a major shift in a school's approach to discipline — may be the answer.

Teaching Positive Behavior

Positive behavior is not taught in a 15-minute session on the first day of school. Nor is a week, or even a month, of reinforcement adequate. PBIS is a systemwide, sustained approach to behavior management, introduced at the outset and reinforced throughout the year.

Abbott Middle School in Elgin, Illinois, uses "Cool Tools" — lesson plans that model expected behavior, explain the reasons for the expected behavior, and allow for student and teacher role play. "Each department is responsible for teaching different procedures at the beginning of the school year," said Matt Freesemann, an 8th-grade U.S. history teacher at Abbott. For example, the math department taught the students how to comport themselves in the stairwells and the bathrooms. "When we saw a dip in the desired behavior, we re-taught the expectations and worked to reinforce them."

Part of the PBIS model of reinforcement comes from acknowledging and rewarding appropriate behavior. One school awards "gotchas" for good behavior, which can be traded for novelties and school supplies at the school's PBIS Store. Another awards "wildcards" for students who are "caught being good." Students take their wildcards to the front office, where they're entered in a raffle — receiving positive feedback all along the way from teachers and staff. Other schools offer a variety of rewards for positive behavior, including lunch with a friend, homework passes, free time in the gym, or a chance to read outside. Schools also hold pizza parties and ice cream socials as incentives for meeting PBIS goals.

There also are consequences — consequences as clear and consistent as the rewards.

At one school, for example, there is a progression of consequences tied to non-violent disciplinary incidents: a verbal warning, followed by contacting the student's parents, then a school conference with the parents and finally a disciplinary referral to the principal's office.

PBIS schools rely on data, tracked most easily in the form of office referrals, to develop and modify their PBIS implementation plan. Using data helps schools stay abreast of trends or patterns in disciplinary incidents: When and where do most office referrals occur? What types of incidents are most common? Which teachers are referring the most students? Which students are most often referred? Are there gender or racial disparities in the referrals?

"It's hard to argue with the numbers," said Kathy Davis, assistant principal at Abbott. "Reviewing the data makes you aware and more conscious of your interactions with students."

At Abbott Middle School, the PBIS Team, consisting of a representative from each grade level and each department, meets monthly to review its disciplinary data and determine its next steps. "It enables us to see where our efforts are paying off and where we need to refocus," Freesemann said. The team's members bring the data to grade level and departmental meetings for further review and planning. "If we see an upward trend in discipline referrals, we can use different incentives to bring things back into line," Freesemann said. "If we notice certain students continue to receive referrals, we can direct more targeted interventions for specific types of misbehavior."

The result?

"We cut our in-school suspensions and after-school detentions in half compared to the first semester last year," Freesemann said. And out-of-school suspensions went from 20 or 25 a year to just three or four.

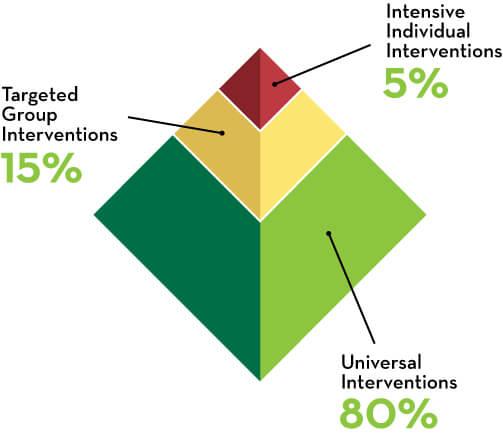

Levels of Support

PBIS schools use a multi-tiered approach to intervention. While the universal supports described above are sufficient to maintain acceptable behavior for about 80 percent of students, 15 percent require more targeted supports to reduce specific misconduct such as truancy. The remaining 5 percent require individualized supports to address more challenging behaviors.

In the second semester, teachers rewarded students on random days and at random times if they were "caught being on time." Students who were late to class had to meet with the principal to discuss tardiness. After several weeks, the number of reported tardies decreased, but there were still 14 students who were consistently tardy. These students required individualized supports.

Abbott set up a four-week program that monitored and rewarded the students' punctuality. The four-week period began with a goal of making it to class on time 80 percent of the time, increasing weekly to 100 percent. As students met goals, they were entered in weekly raffles, with prizes such as T-shirts and movie tickets. Students who met the 100 percent goal earned food cards to local restaurants and graduated from the program.

Ten of the 14 students successfully completed the program. Marisol, a 7th-grader, is one of them. "I love it. It helped me a lot. I don't get any more detentions, and detentions are really boring," she said.

Some of Marisol's friends still get in trouble for tardiness. "I am trying to be as quick as I can. If my friends aren't ready, I tell them I need to go and I leave them now. I wanted to pass the program."

Marisol is no longer tardy and is more engaged at Abbott now. "I want to be a teacher," she said.

Growing Pains

Implementing PBIS and changing a school's disciplinary culture are not easy. Most state PBIS programs will not train a school or district unless there is significant buy-in from teachers and administrators. Research suggests that a school cannot implement PBIS successfully without the commitment of key administrators and 80 percent of the school's teachers. "It's a teacher-focused program," Abbott's Davis said. "Could our teachers implement it without the support of the administration? It would be a lot harder, but yes. Could our administrators implement it without the support of our teachers? Absolutely not."

Securing buy-in from both teachers and administrators is hampered by some common misconceptions about PBIS. First, there is the misperception that PBIS only allows for positive reinforcement and not for other forms of consequences. Second, there is the misperception that positive reinforcement is only allowed to be given in tangible goods such as toys, not in less tangible forms of praise.

There are deeper misgivings as well. Those who have watched half-hearted, failed attempts to implement other disciplinary programs may doubt PBIS's structure or the school's ability to implement it. Teachers are asked to handle more minor disciplinary incidents in the classroom rather than sending students to the principal's office — a fundamental restructuring of discipline in some schools.

School redistricting led to an increase in students exhibiting at-risk behavior at Abbott Middle School. In turn, that led Abbott's teachers and administrators to look for ways to improve discipline.

At Abbott, Davis said, "We introduced PBIS to our teachers as an idea, as a possibility. We tried to show our teachers and staff how flexible the program could really be." Abbott's teachers participated in developing common procedures and expectations for behavior.

"We asked for a lot of input. We gave our teachers a lot of opportunities along the way to shape it," explained Davis. Nonetheless, for those teachers who were totally against changing Abbott's approach to discipline, "we let them know from the beginning that we have to change, no matter what," Davis said. "So, whether you buy into this program or you don't, the mentality has to change or you need to think about looking somewhere else."

Sustained effort, throughout the year, is a key to PBIS's success.

"When we saw lulls in expected student behavior in March or April, we had to keep ourselves as teachers from backsliding to other ways of disciplining students," Freesemann said. "It helped that our principal believed in PBIS 100 percent. When talking to students or parents about disciplinary issues, she always referenced our schoolwide expectations. It really began to change the way we thought about behavior as a school."

PBIS and Racial Disparity in Discipline

Researchers are looking at ways in which PBIS can reduce the racial discipline gap. Too often in many schools, students of color, particularly African American and Latino students, are disciplined disproportionately to their presence in the student body. At Abbott Middle School, PBIS lowered discipline rates while maintaining discipline numbers proportional by race to the school's enrollment.

"As we reviewed the data, we realized we had a few teachers who were sending a disproportionate number of African American students to the office," said Kathy Davis, assistant principal at Abbott. "When we looked at these teachers' disciplinary numbers, we found that they were sending children to the office for incidents which are not grounds for office referrals in our school. In short, once these teachers began to actually implement PBIS, these numbers decreased to where they should be."

Unfortunately, Abbott's proportionality is the exception, not the rule, even in schools implementing PBIS.

Russell Skiba, director of the Initiative on Equity and Opportunity at Indiana University has found that, overall, PBIS has enabled schools to reduce school exclusion by appropriately matching the severity of the disciplinary incident to the consequence. While PBIS reduces school exclusion for all students, Skiba found that students of color in PBIS schools were still more likely to receive harsher punishments for similar misbehavior than their white peers. Nonetheless, Skiba sees promise in the PBIS framework as a means to bring these data and these conversations to the forefront.

Skiba advocates for diverse representation on school PBIS teams to ensure that multiple perspectives aid the development of the school's behavior expectations, interventions, and reinforcement. "I believe educators are excellent problem solvers. If they see a problem, they will try to solve it," Skiba said. "If we bring that kind of awareness into the framework of PBIS, we will see that same kind of problem solving."

Alternatives to Suspension

There are a number of ways that schools can cut down on suspensions so that students do not miss class time. Here are some options:

- Conference with the student to provide him/her with corrective feedback.

- Re-teach behavioral expectations.

- Mediate conflict between students or students and staff.

- Create behavior contracts that include expected behaviors, consequences for infractions, and incentives for demonstrating positive behaviors.

- Student completion of community service tasks.

- Development of an open communication system between parents/guardians and school officials in order to address issues the student may be facing in a collaborative manner.

- Reflective activity, such as writing an essay, about the offense and how it affected the student, others, and the school.

- Loss of a privilege.

- Adjust the student's class schedule or placement to maximize academic and behavioral improvement.

- Create a check-in/check-out intervention plan for the at-risk student with a caring adult in the school who tracks the student's behavioral progress and addresses his/her individual needs on a daily basis.

- Require daily or weekly check-ins with an administrator for a set period of time.

- Refer student to counselor, social worker, behavior interventionist, or Building Based Student Support Team.

- Work with the student to choose an appropriate way for him/her to apologize and make amends to those harmed or offended.

- Arrange for the student to receive services from a counseling, mental health, or mentoring agency.

- Detention or in-school suspension, during which the student completes his/her work.

PBIS and Racial Disparity in Discipline

Too often in many schools, students of color, particularly African American and Latino students, are disciplined disproportionately to their presence in the student body. At Abbott Middle School, PBIS lowered discipline rates while maintaining discipline numbers proportional by race to the school's enrollment.

"As we reviewed the data, we realized we had a few teachers who were sending a disproportionate number of African American students to the office," said Kathy Davis, assistant principal at Abbott. "When we looked at these teachers' disciplinary numbers, we found that they were sending children to the office for incidents which are not grounds for office referrals in our school. In short, once these teachers began to actually implement PBIS, these numbers decreased to where they should be."

Unfortunately, Abbott's proportionality is the exception, not the rule, even in schools implementing PBIS.

Russell Skiba, director of the Initiative on Equity and Opportunity at Indiana University has found that, overall, PBIS has enabled schools to reduce school exclusion by appropriately matching the severity of the disciplinary incident to the consequence. While PBIS reduces school exclusion for all students, Skiba found that students of color in PBIS schools were still more likely to receive harsher punishments for similar misbehavior than their white peers. Nonetheless, Skiba sees promise in the PBIS framework as a means to bring these data and these conversations to the forefront.

Skiba advocates for diverse representation on school PBIS teams to ensure that multiple perspectives aid the development of the school's behavior expectations, interventions, and reinforcement. "I believe educators are excellent problem solvers. If they see a problem, they will try to solve it," Skiba said. "If we bring that kind of awareness into the framework of PBIS, we will see that same kind of problem solving."