Nuri Vargas knows how it feels to be silenced.

Not long ago, while working in a school near San Diego, Calif., Vargas was talking with another teacher when the conversation randomly led to the topic of dental health.

“She said to me, ‘Have you noticed that the Latino kids’ teeth are all rotten? It’s cultural because Latino parents give their kids lots of candy and they don’t brush their teeth.’”

Vargas told her colleague that a lack of health insurance would be a more likely explanation. The other teacher brushed her off with “not all kids, but most of them.”

Although Vargas was concerned that her colleague’s beliefs would trickle over to her treatment of Latino students, she never expressed her concerns to the administration.

“I don’t think I was comfortable with talking to the principal — because what if the principal thought just like her?” she said.

In many classrooms across America, race and ethnicity are very much on the table. Teachers dream of seeing their students discuss difference in a constructive way. Some educators actively encourage their classes to get outside their comfort zones and confront the country’s racial history.

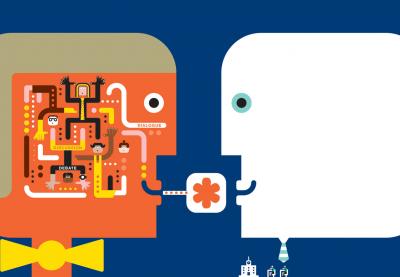

But in many faculty rooms, there’s little to no talk about race. Whether the topic is a racial disparity in students’ academic achievement, a teacher who feels victim to racial discrimination or even simply a question about a black student’s hair, teachers often elect to keep their mouths shut. If teachers can’t have the race talk with each other, how can schools effectively educate their students about difference?

“It’s important for teachers to discuss race with each other for a number of reasons,” said Christine Sleeter, a professor emerita of education at California State University, Monterey Bay and editor of the book Facing Accountability in Education: Democracy and Equity at Risk. Sleeter said teachers and principals need to open the door to dialogue “so schools are able to confront issues of race that have to do with student learning, such as how tracking systems work, who ends up in which tracks and why…And teachers [need to recognize] their own beliefs about the learning abilities of kids and how they overlap with race.”

That teacher sitting next to you in the break room — the one who is too worried to say what she really thinks — may hold the key to higher student achievement. Teachers often fret about their struggles to reach their students and their difficulties in getting parents involved. An honest and collegial dialogue about race, Sleeter says, can help teachers self-analyze their comfort with parents and students and its connection with teachers’ own attitudes about race.

Confronting Race

These days, Nuri Vargas doesn’t have nearly as much trouble talking about race and ethnicity with her colleagues. As a first-grade teacher at EJE Elementary in El Cajon, Calif. — where students learn in a dual-language environment — Vargas feels more open. In the dual-language setting, Latino heritage is always out in the open as a topic for discussion. And Vargas isn’t the only person on the faculty who understands that heritage.

“I’m really comfortable because the majority of us are Hispanic and our principal is Hispanic,” said Vargas. She says she’s no longer dogged by the feeling that anything she says about race or ethnicity will be interpreted in a negative light.

Speaking out can be a lot harder when you’re one of only a handful of teachers of color in your school.

“There is still a pretty high penalty for even going near the topic of race,” said Carmen Van Kerckhove, co-founder and president of New Demographic, a diversity education firm. “There’s always the possibility that you’ll be perceived as playing the ‘race card.’”

In an age of budget cuts and teacher layoffs, teachers often worry that speaking out will lead to a pink slip at the end of the year — or will get them moved into less-desirable position within the district.

“The teacher who’s causing trouble, the principal can displace them,” said Hilton Kelly, a professor of education at Davidson College in North Carolina and a former high school teacher. Kelly studies the experiences of black teachers with a focus on those who work in overwhelmingly white schools. Kelly has spoken with teachers of color in the South who feel they’re suffering the consequences for speaking up about race.

“These teachers are being punished, and a lot of times people are living with it,” he said.

Another barrier to racial dialogue, Van Kerckhove said, is the idea that America is a “post-racial” society. The term “post-racial” seems to have gained prominence during the 2008 presidential campaign, as a way of describing the broad appeal of then-candidate Barack Obama. After Obama’s election, the term morphed into the notion that America has completely gotten beyond racism.

“A lot of people feel like racism is now over, especially with President Obama in office, and that anyone who brings up race is doing it as a shady tactic to get ahead career-wise,” Van Kerckhove said. “So it doesn’t surprise me that even in educational settings, teachers of color are having a hard time broaching the subject.”

The Pink Poodle

For some teachers, putting race into context is a challenge because they don’t understand the situation, or can’t explain it. White people often lack experience in talking about race, largely because they don’t feel marginalized because of race. They fear saying something ignorant or offensive.

“Whites usually don’t have the tools to be able to talk about it very knowledgeably,” explained Sleeter. “We grow up learning that it’s impolite to talk about race.”

White people often don’t even know where to begin the conversation, Sleeter says. “[The reaction is,] ‘What am I supposed to be talking about? What should I even be saying, that’s not going to be totally impolite?’”

Even for teachers of color, labeling an incident or comment as racist is sometimes hard to do.

Hilton Kelly recalls encountering this resistance during his research, when he interviewed black K-12 teachers at predominately white schools.

Timothy, 30, is the only black teacher at his high school. When Kelly asked Timothy if he experienced racism at work, he said “yes.” But Timothy found it difficult to even utter the word “racism.”

Timothy: …I have had a couple of incidents with the administration that I have felt [pause] like racism — the pink poodle syndrome.

Kelly: What is the “pink poodle syndrome?”

Timothy: The pink poodle — you are standing among a crowd of people and you are almost a mascot or a wild one. This is what I get from faculty a lot. It is more annoying than oppressive. “Hey,” somebody might say, “I saw the 60 Minutes report on the war in Africa, what do you think about that?” … I must say that I struggle to say racism only because I don’t want to cheapen the word... I would not want to attach my experiences with a term that I use to describe systemic degradation and deprivation… .

— From “Racial Tokenism in the School Workplace: An Exploratory Study of Black Teachers in Overwhelmingly White Schools.”

Race 101

The dialogue about race should start in the classroom — the teacher-prep classroom, that is. Preservice teachers should be exploring multiculturalism and discussing ways to honor diversity in their future classrooms.

But in many cases, Kelly said, the coursework isn’t giving preservice teachers the tools to speak about race. Even when future teachers take courses on diversity and multiculturalism, Kelly said, those courses don’t take the critical approach to race that future teachers truly need.

“Food, folklore and festivals are not the same as an analysis of race in America,” Kelly argued.

Nor do preservice teachers have the words to explain the racial, ethnic and culturally-based experiences of others.

Tambra Jackson, a professor at the University of South Carolina’s College of Education, used to be one of those silent teachers.

In the beginning of her teacher preparation, Jackson felt silenced in class because, in many cases, she was the only person of color in a predominantly white institution. Race was just not part of the curriculum, she says.

“I was not very vocal in bringing up issues of race in teacher prep,” recalled Jackson. “No one ever discouraged me if I wanted to focus my projects and papers around black culture or other ethnicities, but no one ever encouraged it. And no one ever made that the focus in their teaching.”

Then Jackson experienced a pivotal moment during a summer internship in Cincinnati with the Children’s Defense Fund Freedom School. She gained in-depth knowledge on inequality and education through teaching a social-justice-oriented curriculum.

“That program really helped me to find my voice as an advocate. When I came back that year to do student teaching my professors said, ‘What happened to you?’”

Jackson continued to stay vocal during her professional career. Even as the sole teacher of color at Washington Center Elementary in suburban Fort Wayne, Indiana, she brought race to her colleagues’ attention.

“Because I was the only teacher of color, it got to a point where, I think, my colleagues expected everything that came out of my mouth was going to be about race, diversity, or social justice,” Jackson said.

‘It Starts at the Top’

Jackson also felt comfortable talking freely because she had support from administrators. She came to Washington Center Elementary with a sense of mandate: the area superintendent had encouraged her to apply there. A desegregation order had allowed for children of color to be bussed into the suburban school. While the student body was growing more diverse, Jackson was the only teacher of color.

Jackson was appointed to be the Diversity Index teacher at her school, which meant that she regularly convened a group of students to have explicit conversations about diversity in the school. Working with students on these issues inevitably entailed discussing race with their teachers.

“I knew that I had administrative support outside of the school,” Jackson said about the area superintendent of the school district. “I knew, should I have any issues, I had someone I could go to… I think the administrator knew that also.”

Administrator support or willingness to encourage racial discourse can have a huge impact in the work environment for teachers.

“This is one of those things that definitely starts at the top,” said Carmen Van Kerckhove of New Demographic. “When the leadership is on board and really understands the issues, it makes it a lot easier to trickle down.”

Van Kerckhove advises administrators not to rush head-on into complicated discussions of racial inequality because some may not be ready to handle it. Take into account your staff’s and school’s comfort level with race, she says, and go from there.

Jackson suggests principals break the ice by telling groups, especially diverse groups, from the start that the discussion will be hard, but that having these talks is a commitment the school needs to make. Then principals need to follow up with action.

“Frame the discussion in terms of starting with basics people can get their heads around,” recommends Christine Sleeter. She uses the example of an elementary school administrator, who told Sleeter how she used data to get teachers talking about race and ethnicity.

“It took her a lot of work just to get the teachers to begin to say we have a racial achievement gap in this school,” Sleeter says. The administrator opened up conversation by simply giving teachers test scores and asking them to look at it. “She asked the teachers, ‘What do you see is the pattern there?’ When teachers were starting to say, ‘I see the white students are achieving better than the Latino students,’ for them that was a step forward.”