This school year brings another set of civil rights 50th anniversaries that deserve respect and recollection. From Freedom Summer to the passage of the Civil Rights Act, 1964 is thought of by many people as the final climb toward passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, but that's an oversimplification that doesn't do justice to the year's complexity. The most important lesson your students can learn from 1964? That the quest for racial equality and justice continues. Victories should be celebrated, yes, but never should we lose sight of the need to keep moving forward.

Voting Rights

As 1963 ended and a new year began, it was clear to civil rights activists that securing the vote, and thus the power to create change, was essential. On January 23, 1964—almost 100 years after the 15th Amendment extended voting rights to African Americans—the 24th Amendment was ratified. It eliminated poll taxes, a common tactic used to prevent black citizens from participating in elections. But on the ground, little changed for African Americans living in communities in which literacy tests, employer pressure and outright intimidation continued unabated.

Civil rights activists knew it would take more than legislation to truly open the polls to black citizens. An impressive cross-racial push for education, voter registration and participation in the upcoming presidential election was launched—the 1964 Mississippi Freedom Summer project. Nearly 1,000 mostly white, mostly Northern college students volunteered and were trained in techniques of nonviolent resistance.

Under the direction of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and other civil rights organizations, the volunteers ran health clinics, established Freedom Schools to educate and empower African Americans and sponsored voter-registration drives. Volunteers also worked to establish the inclusive Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) to challenge the all-white Mississippi Democratic Party delegation.

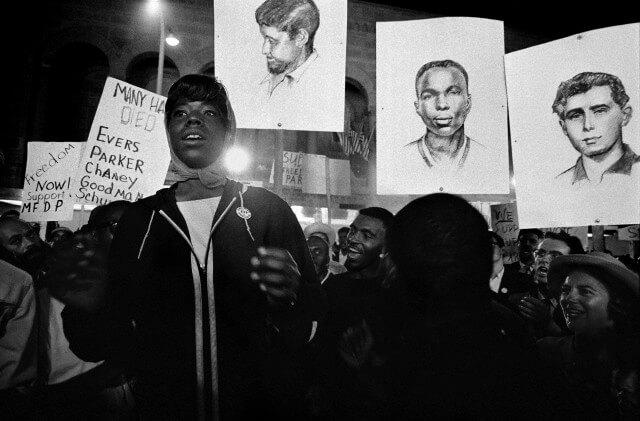

On June 21, 1964, the day after the first Freedom Summer volunteers arrived, three volunteers went missing after driving to check on a black church that had been destroyed by arson. James Chaney was a local activist from Mississippi; Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner were white college students from New York City. Their mutilated bodies were found weeks later in Philadelphia, Miss. The mob of Ku Klux Klan members that killed them included local officials.

The nation was outraged. The horrific death of white college students finally drew the country’s full attention to the daily brutality and terror tactics used in the South to prevent black people from registering to vote.

That attention remained focused on the civil rights movement in August as the MFDP delegates arrived at the nationally televised Democratic National Convention—where they were prohibited from taking their seats.

Delegate and sharecropper Fannie Lou Hamer protested the DNC’s discrimination from the convention’s floor. “All of this is on account of we want to register, to become first-class citizens,” she said. “And if the Freedom Democratic Party is not seated now, I question America. Is this America, the land of the free and the home of the brave, where we have to sleep with our telephones off the hooks because our lives be threatened daily, because we want to live as decent human beings, in America?”

Her impassioned speech didn’t win the MFDP all its seats, but it struck a powerful blow against the false perception that the 24th Amendment had ended voter suppression in the South.

De Jure Segregation

Despite some victories, businesses and public spaces in most of the South remained segregated by law and custom. In St. Augustine, Fla., local activists had been fighting to end segregation and discrimination for several years. They appealed to Martin Luther King Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) for assistance and, in the spring, the SCLC responded by launching a campaign. King hoped to support ongoing local efforts and to garner national support for the proposed Civil Rights Act, which had been stalled for months by filibustering and other tactics.

Confrontations took place at segregated hotels, restaurants and beaches. Black and white activists from all over the country faced violent opposition in St. Augustine throughout the spring and summer. Many were jailed, including a group of clergy invited to the city by King. Sixteen jailed rabbis wrote a letter expressing solidarity with the quest for justice: “We came as Jews who remember the millions of faceless people who stood quietly, watching the smoke rise from Hitler’s crematoria. We came because we know that, second only to silence, the greatest danger to man is loss of faith in man’s capacity to act.”

The rabbis’ sentiments echoed across the rest of the country, blending with the public outcry over the violence in Florida and the atrocities committed against Freedom Summer volunteers in Mississippi. This heightened awareness helped secure the support that led to passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 on July 2. Segregation in businesses and public places and discriminatory employment practices were finally outlawed. But, it would take many years of litigation and social action before real change was seen in communities.

White Supremacy in the North

The civil rights movement and the South are inextricably linked in most people’s minds, but in 1964, activists were realizing that white supremacy could manifest as systems of inequity in the North that were far less visible than the Jim Crow laws of the South.

On the surface, life in the North seemed freer, but discrimination was just as prevalent. As upwardly mobile white families moved to suburbs, many African Americans were trapped in crumbling inner-city neighborhoods. Poverty, along with housing policies such as red-lining and restrictive covenants, kept black families living in urban neighborhoods from which the white middle class had fled. Following the residential patterns, schools in those neighborhoods suffered from de facto segregation, the kind that Brown v. Board of Education hadn’t addressed. All-white police forces in the North didn’t resort to fire hoses as Bull Connor had done in Birmingham, but they often used brutal methods to deal with black residents.

In February 1964, parents and schoolchildren in New York City participated in a citywide boycott of the public school system to demand integration. In a handful of other Northern cities, rioters expressed outrage at police brutality and discrimination.

Impatience for real change was growing, and new voices in the movement called for black power and black pride. This new group of activists questioned King’s approach, especially in the North. On June 28, at the founding rally of the Organization of Afro-American Unity, Malcolm X set aside King’s tactics and proposed his own, saying, “Tactics based solely on morality can only succeed when you are dealing with people who are moral or a system that is moral. A man or system which oppresses a man because of his color is not moral. It is the duty of every Afro-American person and every Afro-American community throughout this country to protect its people against mass murderers, against bombers, against lynchers, against floggers, against brutalizers and against exploiters.”

Never Rest

As 1964 came to a close, King was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. In his acceptance speech, King questioned the honor. He described the vicious opposition that nonviolent protesters continued to face as well as a persistent lack of opportunity and poverty.

“I am mindful that only yesterday in Philadelphia, Mississippi, young people seeking to secure the right to vote were brutalized and murdered. And only yesterday more than 40 houses of worship in the State of Mississippi alone were bombed or burned because they offered a sanctuary to those who would not accept segregation.”

His message is an essential one, even 50 years later. When justice is the goal, celebration is secondary. The focus must always be forward—toward a day when small victories will finally converge and, in the words of King, “Let justice roll down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream.”

Timeline

January 23

Ratification of 24th Amendment

February 3

NYC school boycott

March

Southern Christian Leadership Conference campaign in St. Augustine, Fla.

June

Mississippi Freedom Summer Launch

June 21

Murder of Chaney, Goodman and Schwerner

June 28

Malcolm X speech at founding rally of the Organization of Afro-American Unity

July 2

Passage of Civil Rights Act of 1964

August 24-27

Democratic National Convention

December 10

King’s Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech