By seventh grade, Jerome had a reputation: weak performance on assessments, inconsistent homework, frequent need for redirection in class, inappropriate comments at school and online, physical fighting.

But I saw a different Jerome.

In English class, Jerome was always raising his hand to read aloud or to contribute his insights, even during the Shakespeare unit, when he struggled with the language. He loved to learn! While he often missed basics in his writing, like using evidence to support his thesis, he used every assignment to explore topics that mattered to him—his relationship with his brother, his leadership in a neighborhood trash cleanup, his admiration for a classmate’s perseverance, his experiences playing baseball. As he developed his writing voice, he started to ask for and incorporate feedback, grow from mistakes and listen more openly and compassionately to his peers.

In eighth grade, Jerome got into trouble again. It was the last disciplinary straw, and school officials “had to evaluate his continued enrollment.”

Within Jerome is a kid able to disrupt and derail an expertly run classroom. And within Jerome is a kid who works extraordinarily hard and has dealt with more than his share of pain and abandonment. Couldn’t we accept the hurt, angry and impulsive parts of Jerome in the service of educating all of him? Of course there are details I don’t know, and I can’t say whether the school’s decision was or wasn’t best for Jerome or his teachers and classmates. What I do know is that a student who needed compassion and healing and who’d worked so hard was removed from his community. And I was an agent of that community.

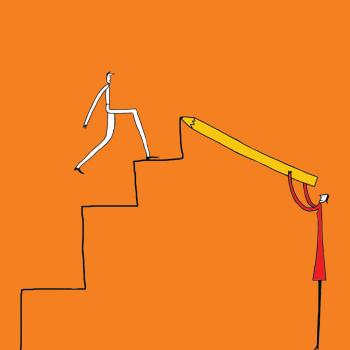

Psychologist Brett Litz and his colleagues define “moral injury” as “perpetrating, failing to prevent, bearing witness to, or learning about acts that transgress deeply held moral beliefs and expectations.” The concept is usually applied to war veterans, and I’m not comparing my job to a soldier’s or Jerome’s leaving school to an act of war. Yet I do have a deeply held moral belief in helping all students thrive and in cultivating a sense of belonging. Even if Jerome would get a fresh start at a new school, I couldn’t escape the feeling that I might have been able to do something that would have led to a better outcome. If standing by while a student is forced to leave school is a kind of moral injury, how do teachers recover?

Showing Self-Compassion

As teachers who care, we open ourselves to feelings of sorrow when our students mess up, and despair when our schools make decisions we can’t influence and don’t understand. We might begin to think of ourselves as failures or feel our work must not matter. We might even judge our own grief.

“Why do I feel so sad?”

“What’s wrong with me?”

“These things happen.”

“Get over it.”

I thought all of these things after Jerome left. I still sometimes do.

Building strong relationships means that I can better work with my students to determine the feelings behind the behaviors.

Dr. Kristin Neff writes in a Psychology Today blog post that self-compassion has three components: “being kind and caring toward yourself rather than harshly self-critical; framing imperfection in terms of the shared human experience; and seeing things clearly without ignoring or exaggerating problems.” When our institutions behave in ways that go against our values, we can give ourselves the support we’re so good at giving our students. We can remind ourselves that our hard work was worthwhile and allow ourselves to grieve our losses. We can think about how we’ve acted consistently and inconsistently with our own values so we can make conscious decisions about what to do next. I couldn't escape the feeling that I might have been able to do something that would have led to a better outcome.

Maintaining a Connection to the Student

One step can be finding creative ways to keep supporting students who no longer have access to our institutions. One way I can stay in touch with Jerome is by reading and responding to his writing. Since I’m no longer his teacher, I can respond to his work purely as an interested reader and helpful critic. I can also offer to write recommendation letters. I can advise his family about his educational path. I can tutor him. I can send him information about conferences, contests and leadership opportunities. I can show Jerome that I remember him, care about him and am still here for him.

Recommitting to Students Who Are Still Here

Some days, I still have trouble coming to work at the school that kicked Jerome out. But if I take a sick day when I’m not actually ill or show up for class physically but not mentally, then I’m not really present for the rest of my students. Avoiding my own pain means also avoiding some of the values that bring meaning and vitality to my work and that made a difference for Jerome: creating authentic connections and a sense of belonging, and fostering an environment where students can be creative and take risks.

In the months since Jerome left, I decided to recommit myself to my work. I developed a model-building project to help my students understand A Midsummer Night’s Dream. I worked on my advisory curriculum and got to know my students better. I asked Nina about the gothic fiction she reads, joked around with Winston and shared in Doug’s fascination with hot-glue sculpting. I gave them all feedback on their writing to show I heard them and cared about their growth. Even when I feel angry or sad or numb—especially then—I can acknowledge those feelings and keep teaching in ways that serve my values.

Working Toward Responsive Discipline

Every disciplinary incident I’ve seen in 15 years of teaching was much more complex than a bad kid doing a bad thing. If Jerome got into a fight or used inflammatory language, what was the function of those behaviors? The desire for attention? For social acceptance? An inability to cope with difficult thoughts and feelings? Was Jerome ever taught behaviors that would serve those same functions in a more positive way? Now that he’s gone, I’m thinking about other students who are behaving in ways deemed unacceptable. I’m focused on how my school community can understand the functions of those behaviors and teach behaviors that serve the same functions in more positive ways.

It starts in the classroom by taking time to know my students, where they’re coming from, what they’re dealing with. Building strong relationships means that I can better work with my students to determine the feelings behind the behaviors. It also means using a culturally responsive, student-centered curriculum to foster empathy among students and implement strategies that hold them accountable to each other. This is a great place for the administration to get involved too. Peer mediation and restorative justice practices are alternatives that can keep kids in class and in our school community, fostering a culture rooted in development rather than punishment.

Showing Compassion to School Leaders

I might find it tempting to say I would never do something so heartless (or damaging or stupid … insert your choice of adjective). But no one wants to ask a student to leave a school. It’s not like my school’s administrators came to their decision about Jerome lightly, and they have information about his situation that I don’t. And no one—no teacher, administrator or student—always heads in the direction of their values. That doesn’t make us heartless or stupid; it makes us human.

I can express my feelings of grief to my administrators and ask how they feel. Maybe they’re hurting as much as I am. Maybe neither of us has to suffer alone. I can also look for growth opportunities. What else could we, as a school community, have done to help Jerome find his way at our school? How can we help other kids now? And finally, just as I can recommit to my own values, I can help my administrators clarify and recommit to theirs. We really are in this together.

Recovery doesn’t negate the injury. None of these actions will bring Jerome back or take away my disappointment and anger now that he is gone. But they’ll allow me to continue teaching in a way that helped Jerome find his voice, and that’s the teacher I want to be.