In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Mexican Americans/Chicanos across the state of Texas made their voices heard in a civil rights movement that would change the state forever. Few people know that the movement began when students in a small farming community took action in a dispute over who could and couldn't be a high school cheerleader.

I witnessed that movement from a front-row seat, as a teacher in Crystal City, Texas.

In 1969, Mexican Americans were prohibited from speaking Spanish in school. There were no classes or lessons about Mexican history, culture or literature. The contributions of Mexican Americans were not included in textbooks.

Mexican Americans were — and remain — the overwhelming majority in Crystal City.

At the time, nearly half of these were migrant farmworkers. In spring, migrant parents took their children out of school, often before the semester had ended, and sometimes didn't return from the migrant circuit until after the fall semester had started.

During that summer interim, local government and school officials — all representing the Anglo minority — would select candidates for fall elections and pass measures, rules and regulations to maintain control of the absentee majority.

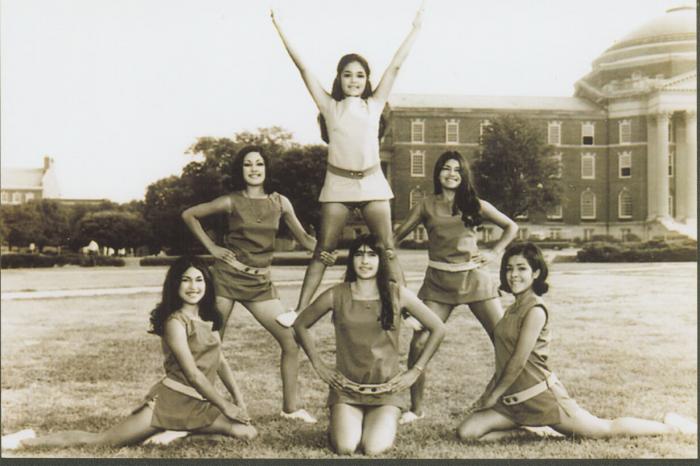

The city council wasn't the only place where the Anglo minority was overrepresented. If you looked at the local high school's cheerleading squad, you would never know that most people in Crystal City were Mexican American. While school cheerleaders had been elected in the past by the student body, once Mexican American youth became the majority in the schools, the rules were changed. A faculty committee now decided the selection. Only one Mexican American cheerleader was allowed, while the other three positions were only for Anglos.

In 1969, when two cheerleader positions were vacant, Chicano students were told they could not fill the vacancies since their quota of one had been met. The school board also imposed a requirement that any candidate for cheerleader had to have at least one parent who graduated from the high school.

Mexican American students cried foul. School administrators did not help, so students met with the superintendent, who decided on what he considered a more equitable quota system: the selection of three Anglos and three Mexican American cheerleaders.

Anglo parents protested against the superintendent's "caving in" to Chicano student activists. The school board nullified the superintendent's concessions and added an incendiary resolution that any future student unrest would be met with expulsion.

Student leaders took their concerns to the school board.

"Boy, you're out of order!" shouted one board member, as one student began to address the board.

The board then refused to hear the students' demands, which included recruitment of more Hispanic teachers and counselors; more classes to challenge students and fewer shop and home economics electives; bilingual-bicultural education at the elementary and secondary levels; Mexican American studies classes to reflect the contributions made by Latinos; and the addition of a student representative to the school board.

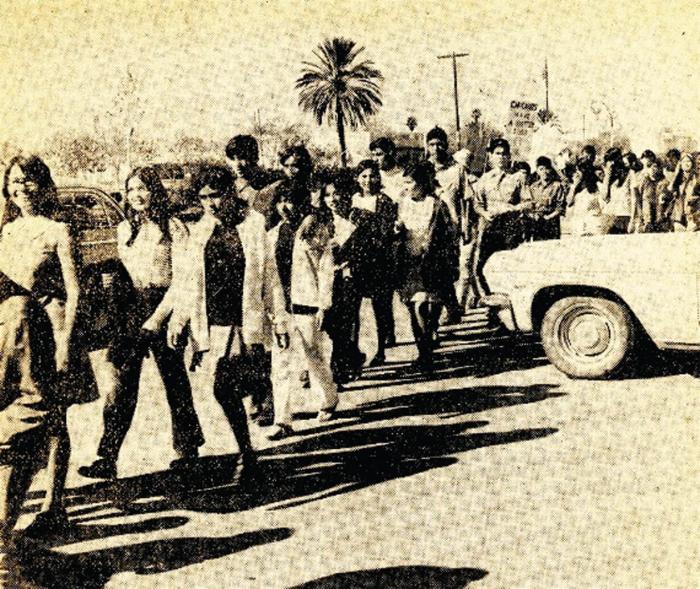

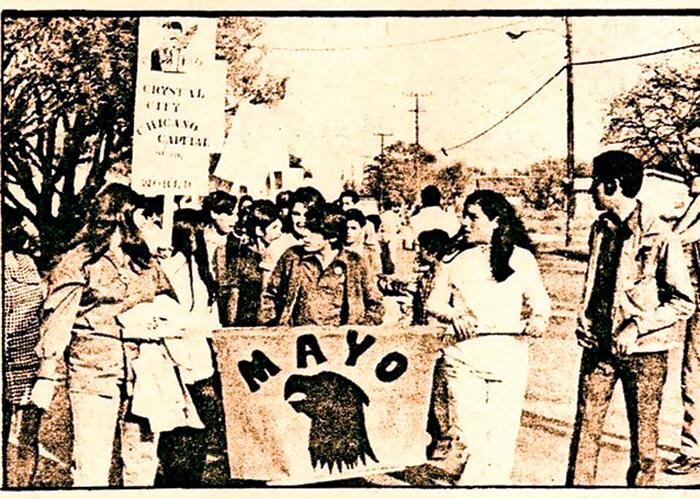

Frustrated and intent on making their case known, high school students staged a walkout on Dec. 9, 1969. More students joined each day, until more than 2,000 students were walking the picket line.

Once junior high and elementary students joined their brothers and sisters in solidarity, the Texas Education Agency (TEA) sent negotiators to end the walkout and get the students back in school. The board, however, continued to play hardball and nixed the TEA proposal to close the schools early for the Christmas holidays.

By then, the media had descended on the town. Mexican Americans in neighboring South Texas towns beset with similar issues of discrimination identified with the student walkout in Crystal City.

Texas Sen. Ralph Yarborough invited three student leaders to Washington, D.C., to discuss the discrimination in their schools. They also met with Sen. Edward Kennedy and Sen. George McGovern, who in turn alerted officials in the Civil Rights Division of the Department of Justice and the Department of Health, Education and Welfare of the serious situation in Texas.

Back home, Texans for the Educational Advancement of Mexican Americans (TEAM) mobilized educators to Crystal City to teach the striking students during the holidays. Since the schools were closed, they met in a community dance hall.

I was one of the teachers who answered the call to tutor the striking students. I was immediately taken by the poise and confidence of the striking students, but more impressed by their eagerness to learn. I was humbled when the students asked if I would return to teach once the walkout was over. I told them I would seriously consider it.

Overwhelmed by the pressure, the board finally held a hearing. On Jan. 9, 1970, student demands were reluctantly approved. The hard-fought student victory energized and educated the community. In the spring, Mexican American candidates swept the school board and the city council elections.

And in September, keeping my promise, I joined the Crystal City schools as an elementary bilingual teacher. The following year I moved to the high school as the Senior English teacher.

Within two years, the schools' faculty, administrators and superintendent reflected the Mexican American majority of the community. More students were finishing school; a majority of the graduates were attending some form of higher education. Crystal City graduates were receiving acceptances from Harvard, Stanford and the University of Texas, as well as local area junior colleges. Some of those student leaders have gone on to hold key positions at the school and in state government.

The Crystal City student walkout remains a high point in the history of student activism in the Southwest. Crystal City provided both template and inspiration for any community faced with economic or civil discrimination.

Above all, it gave us participants a sense of individual and communal destiny in the knowledge that a common cause can bring about justice, unity and change.

In the rallying cry of the United Farm Workers and the more recent U.S. immigration reform protests: "Sí, se puede."

Yes, we can.

Discussion Questions

1. Barrios notes that many of the students involved in the walkout went on to attend Harvard, or attained prominent positions in government. Why does he point this out? Why would Harvard be interested in students who participated in the walkout? Why would these students be more likely to achieve success later in life?

2. Crystal City students wanted to see Mexican American subjects addressed in the classroom. How well do the lessons in your classroom reflect the world you see every day?

3. How did the Anglo minority manage to control a town that was mostly Mexican American? Do you think similar things are going on today?