On a muggy August morning in 1790, President George Washington sailed to Newport, R.I., with Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson and other dignitaries. Three months earlier, Rhode Island's legislature had made it the last state to ratify the United States Constitution, and Washington was eager to gain support for the amendments that would later become the Bill of Rights.

The group was greeted by Newport’s politicians, businessmen and clergy and, together, they gathered at a red-brick customs house where representatives of the community addressed the president.

Among them was Moses Seixas, who read two letters—one as the grand master of the Masonic Order of Rhode Island and the other as the warden of Newport’s Hebrew Congregation.

It’s hard to overstate the significance of the moment. Much of Newport’s Jewish population had come to America to escape centuries of persecution in Europe. And Seixas’s opportunity might have happened only in Rhode Island, which was founded by Roger Williams in 1636 as a haven for religious dissenters. Outside the colony, freedom of religion for non-Christians was hardly a given. In fact, the freedom to worship for many nonmajority Christians—including Quakers, Baptists and Catholics—was nearly as precarious.

In the early days of the United States, religious minorities had several concerns: Would they be allowed to practice their religion? Would they be allowed to build houses of worship? Would they have the same political rights as members of mainstream Protestant sects? After all, it was within living memory that “heretics” had been banished and even burned at the stake. And, in 1790, many of the states excluded Jews, Catholics, Quakers and others from civic participation on the basis of religious differences. Even in Rhode Island, Jews could not vote or hold public office.

In this context, Seixas read his message to Washington on behalf of Newport’s small Jewish population:

“Deprived as we heretofore have been of the invaluable rights of free Citizens, we now (with a deep sense of gratitude to the Almighty disposer of all events) behold a Government … which to bigotry gives no sanction, to persecution no assistance.”

The courteous thing for the president to do was to respond in writing. But what would he say? Then, as now, disputes over religion had the potential to dissolve into controversy.

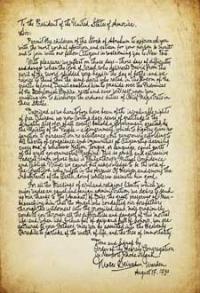

Letter To the President of the United States of America

To the President of the United States of America

Sir:

Permit the children of the Stock of Abraham to approach you with the most cordial affection and esteem for your person & merits and to join with our fellow Citizens in welcoming you to New Port.

With pleasure we reflect on those days—those days of difficulty and danger when the God of Israel, who delivered David from the peril of the sword, shielded your head in the day of battle: and we rejoice to think that the same Spirit who rested in the Bosom of the greatly beloved Daniel enabling him to preside over the Provinces of the Babylonish Empire, rests and ever will rest upon you, enabling you to discharge the arduous duties of Chief Magistrate in these States.

Deprived as we heretofore have been of the invaluable rights of free Citizens, we now (with a deep sense of gratitude to the Almighty disposer of all events) behold a Government, erected by the Majesty of the People—a Government, which to bigotry gives no sanction, to persecution no assistance—but generously affording to All liberty of conscience, and immunities of Citizenship: deeming every one, of whatever Nation, tongue, or language, equal parts of the great governmental Machine: This so ample and extensive Federal Union whose basis is Philanthropy, Mutual Confidence and Publick Virtue, we cannot but acknowledge to be the work of the Great God, who ruleth in the Armies Of Heaven and among the Inhabitants of the Earth, doing whatever seemeth him good.

For all the Blessings of civil and religious liberty which we enjoy under an equal and benign administration, we desire to send up our thanks to the [Ancient] of Days, the great preserver of Men—beseeching him, that the Angel who conducted our forefathers through the wilderness into the promised land, may graciously conduct you through all the difficulties and dangers of this mortal life: and, when like Joshua full of days and full of honour, you are gathered to your Fathers, may you be admitted into the Heavenly Paradise to partake of the water of life, and the tree of immortality.

Done and Signed by Order of the Hebrew Congregation in Newport Rhode Island

Moses Seixas, Warden

August 17, 1790

Dueling Identities

In 2012, Americans belonging to minority religions as well as those who believe in no religion still struggle to claim a place in the public square. According to the Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life, more than 2.2 billion people—more than a third of the world’s population—face religious restrictions. They live either in nations where the government restricts worship or where social hostilities force them to defend their beliefs. Even in the United States, there has been a long debate about the role that religion should play in our national identity, and research suggests that we know very little about each others' faiths, traditions and practices.

Lack of knowledge can lead to misunderstanding and distrust. Echoing debates in Europe, head coverings have come under suspicion in schools, government buildings and motor-vehicle licensing bureaus. The effort to build an Islamic center near New York City’s Ground Zero memorial caused a firestorm of debate. A poll taken in July 2011 revealed that 22 percent of Americans would not vote for a Mormon for president, regardless of that candidate's policies or record.

It’s in this environment that students can benefit from learning about Washington’s response to Newport’s Hebrew Congregation.

Washington’s Words

Writing back just four days later, the nation’s first president reassured the Jewish community of Newport that his government “gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance.” He went further, explaining the difference between mere forbearance and true freedom:

“It is now no more that toleration is spoken of, as if it was by the indulgence of one class of people that another enjoyed the exercise of their inherent natural rights.” Washington envisioned that in the new nation, members of all religions would be able to practice their individual faiths by right—not through the permission or indulgence of the majority.

“All possess alike liberty of conscience and immunities of citizenship,” Washington wrote, defining religious freedom as a natural right preceding any constitution or laws.

Washington's letter is a clear example of his intent to establish a nation in which the government upholds principles of religious freedom. But it is not an isolated document. He had also written letters to the nation’s Quakers, Catholics and Baptists. And his peers, including Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, held similar views. In a letter to the Danbury Baptist Association in Connecticut 12 years later, Jefferson wrote:

“Believing with you that religion is a matter which lies solely between man and his God, that he owes account to none other for his faith or his worship, that the legitimate powers of government reach actions only, and not opinions, I contemplate with sovereign reverence that act of the whole American people which declared that their legislature should ‘make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof,’ thus building a wall of separation between church and state.” (See our online portfolio for the full text.)

Washington’s letter is particularly important given the contemporary debate over the the Bill of Rights and its First Amendment. Just a year later, the states ratified the amendment understanding that it set a framework for religious freedom. Washington also offered something equally important: a moral vision that balances respect for religious difference with the responsibilities of citizenship.

Letter from George Washington to the Hebrew Congregation at Newport

Letter from George Washington to the Hebrew Congregation at Newport

Gentlemen:

While I receive with much satisfaction your address replete with expressions of affection and esteem, I rejoice in the opportunity of assuring you that I shall always retain a grateful remembrance of the cordial welcome I experienced in my visit to Newport from all classes of citizens.

The reflection on the days of difficulty and danger which are past is rendered the more sweet from a consciousness that they are succeeded by days of uncommon prosperity and security. If we have wisdom to make the best use of the advantages with which we are now favored, we cannot fail, under the just administration of a good government, to become a great and happy people.

The citizens of the United States of America have a right to applaud themselves for having given to mankind examples of an enlarged and liberal policy—a policy worthy of imitation. All possess a like liberty of conscience and immunities of citizenship. It is now no more that toleration is spoken of, as if it was by the indulgence of one class of people that another enjoyed the exercise of their inherent natural rights. For happily the Government of the United States, which gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance, requires only that they who live under its protection should demean themselves as good citizens in giving it on all occasions their effectual support.

It would be inconsistent with the frankness of my character not to avow that I am pleased with your favorable opinion of my administration and fervent wishes for my felicity. May the children of the stock of Abraham who dwell in this land continue to merit and enjoy the good will of the other inhabitants—while every one shall sit in safety under his own vine and fig tree, and there shall be none to make him afraid. May the father of all mercies scatter light, and not darkness, in our paths, and make us all in our several vocations useful here, and in His own due time and way everlastingly happy.

G. Washington

August 21, 1790

A Story with Universal Lessons

The story of George Washington and Moses Seixas is that of a particular cultural setting and the challenges faced by a unique religious community. And clearly, despite Washington’s intent, many religious minorities still dream of worshipping in environments that have achieved, at the least, a degree of toleration. But educators can help students achieve a connection between that event and those of the present day.

Facing History and Ourselves and the George Washington Institute for Religious Freedom believe these important documents—and the lessons they offer about pluralism and democracy—are a great place to begin.

Deborah Conway, a teacher at the Facing History School in New York City, found the documents fascinating—as did her students.

“[The letter] was written so long ago, and yet here was a president expressing his views about religious tolerance,” she says. Her students wrote their own letters to Washington from a modern-day perspective, communicating examples of how Americans still struggle with these issues. The school’s proximity to the planned Islamic center near the Ground Zero memorial, she says, “definitely sparked” much of their discussion.

The goal is for students to experience what German philosopher Jürgen Habermas calls a “mutual recognition and mutual acceptance of divergent worldviews”—a “kind of tolerance [that] allows religion and democracy to coexist in a pluralistic environment.”

Editor’s note: Different transcriptions of these letters provide differing punctuation, differing capitalization and, in some cases, slightly different wording. We have replaced some outdated usages for clarity while trying to preserve the original tone of the letters.