Vishavjit Singh is an engineer, writer, educator, activist, costume player and the artist behind Sikhtoons.com. A crusader for cross-cultural understanding, this real-life superhero spoke with Teaching Tolerance about using his powers to dispel myths about Sikhs and to encourage a new generation of comic book artists to share their stories.

How did you come to cartooning?

For me cartooning really came out of a tragedy: 9/11. For America it was life-changing, and for me, I was the target of so much hate and bias. One of the first victims killed in a hate-crime wave after 9/11 was a Sikh out in Arizona. And I personally know friends who were taken out of trains, who were chased off highways by people, so it was a rough time.

And I remember a few weeks after 9/11 there was this cartoonist, Mark Fiore. He created a cartoon called “Find the Terrorist,” and it was basically these rotating animated images where he was trying to make the point that you have Muslims or Hispanics or Sikhs, a lot of different shades of brown people in the U.S., [who] are not terrorists.

Something just got inside my head, and I said, “OK, Mark did it once, but he’s probably not going to create too many other cartoons with Sikhs or somebody who looks like me. Maybe I should start doing it!” So I started creating cartoons, and months later created a website, Sikhtoons.com, to house all my work.

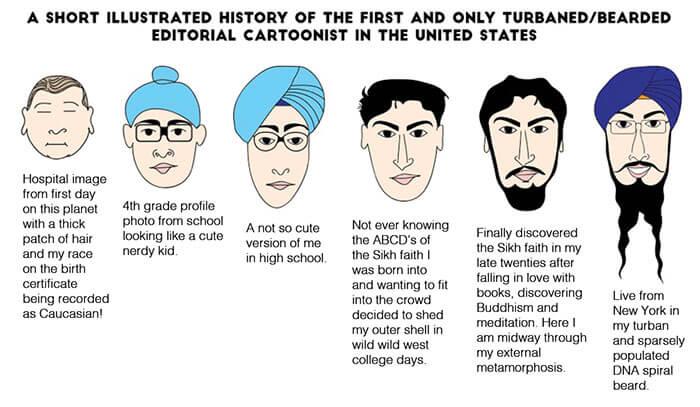

Since then, I have been creating cartoons inspired by the news or my own experiences focusing on Sikhs in America, Canada, wherever. And I got a global fan base because it’s just one of those art forms that hasn’t really existed within certain communities. Most people don’t see turbaned, bearded characters in cartoons.

Tell the story of how you transformed yourself into Sikh Captain America.

It was a purely accidental journey. Three years ago, I made my first trip to New York City Comic Con as an exhibitor. I knew I had this brand-new audience; most of them probably don’t know who I am. They presume, as many people do when they see me with my turban and a beard, [that] I’m not American, I’m not from here.

So I thought, I have to create a marketing kind of poster that is going to sit behind my booth to somehow visually tell people, “Hey, look at my work, come over and let’s have a conversation.”

This is the summer when the first Captain America movie came out, and I was like, you know what? There’s not a more American superhero than Captain America. I’ll create this illustration of a Sikh Captain America, a guy with a turban and beard, and a really catchy caption: “Let’s kick some intolerant ass!”

People loved it. I had tons of people taking photos and coming over to ask me, “Hey, so who are you? What are you doing?”

A photographer was passing by and she was working on photography project to capture Sikhs in America just doing normal things, [being] farmers, mothers, fathers, whatever they do. In passing she mentioned to me, “Maybe next year you should come back to the comic con in the costume.” And I flat out said, “No way.”

I’ve been bullied as a skinny boy all my life, so I could not envision myself wearing a costume. Then a year passed by, and the Milwaukee massacre happened at a Sikh temple. I wrote an op-ed piece in The Seattle Times making the argument that we need a superhero in comic books who fights hate crimes.

And the photographer happened to read that piece and she came back to me by email and said, “This is a wonderful piece—would you reconsider your decision?” And then at this point, I was like, “Well ...” I was still uncomfortable. I have body-image problems, which we usually don’t associate with men. But I just felt circumstances had changed, so I said “Sure, why not.”

The photographer bought this costume for me. I was so uncomfortable; I was like, “Man, this is not going to work.” I actually went to Sports Authority to buy padding that they use for baseball and football to see if I could somehow stuff it under my costume and make myself look big.

My wife [said], “If you’re going to do Captain America, you go out as who you are.” So I stepped out. I was super nervous because I’m thinking, “OK, I’m skinny and I’m wearing this skintight costume, and on top of that, I am turbaned and bearded. I don’t know how people [will] respond to it.”

As it turned out, I was just amazed how well people received me. It blew me away. I had police officers that came up to me to take photos. I got pulled into weddings, wedding parties, professional photo shoots, people being like “Hey, can we take a photo with you?” So there was a transformation that I’ve never experienced as a turbaned and bearded man because people usually act sort of scared, or apprehensive. So this was like somebody had flipped a switch, and suddenly—I mean, people were hugging me! So yeah, it was quite a transformation.

Why do you think people are so drawn to Sikh Captain America?

I think it’s a couple of elements. One is comics are a very American creation. They do exist in other parts of the world, but we are a young nation; we don’t have our own mythology. A lot of us grew up with comics and, in many ways, for us comic books are an essential mythology that we have. And a lot of comic books and superhero characters were created by immigrants who were Jewish, who were escaping persecution in Europe. I think there’s a certain fascination we have with these superhero-like characters who single-handedly go do amazing things and fight bad guys and bad voices.

So that’s one element. And then, of course, it’s Captain America, who is the quintessential American superhero. And when [people] see me, they don’t expect a turbaned little guy in the Captain America costume. They realize that they perceive me on the negative side of the spectrum—and then, suddenly, when they see Captain America, they are forced to kind of see, “Hey, maybe this is his expression of patriotism: He is as American as we are!” And I guess people also see the point that “American” is not defined by looks. There is no such thing as an American look. We come in all hues and shapes and sizes.

Why do you think young kids at your workshops react so well to you?

All kids are a little different, [but] they’re just absolutely mesmerized by the fact that I have a shield with me. And they’re so honest—they’re like, “I don’t have a problem with the turban, I don’t have a problem with the beard, he just needs to kind of bulk up, and maybe have better shoes.”

One thing that I do with kids is I usually ask them, “Where do you think I’m from?” And most kids, they don’t say I’m from here, they all have different ideas. “Africa!” “Asia!” And when I tell them that I was actually born here, they’re like, “Really?” And the amazing thing is that this comes from kids who are of all ages and backgrounds, some of them not even born here in the U.S. Unfortunately, we live in that reality where being turbaned and bearded is kind of seen as this ultimate other.

I do interactive workshops where I showcase some of my work, and then I ask the participants, anywhere from 3- or 4-year-olds to teenagers, “I want you to create cartoon illustrations. I want you to use your imagination and I want you to personalize it, meaning I want you to think about your sphere of circles: family, friends, teachers, people who inspire you or who you look up to. Create superheroes out of them, create comic characters out of them.”

I want them to [know], “If I can do cartooning, certainly you can do it too.” And then I also showcase my work, which is very personal at times in my own life. My message to these guys is, “Create work in words or in pictures that are informed by your life. Bring your story into it.

I want you to think about people you look up to. Create superheroes out of them.

How does the style of art you do work with the messaging you put out there?

I think for a lot of kids and even adults, they might not realize it, but just by seeing [an] image on a poster or on a computer screen, it goes in our subconscious and it’s like this new data point that creates a new universe where now we can envision a black Captain America or a turbaned, bearded Captain America.

Captain America is an imaginary character; he’s fictional, right? And yet when I don that uniform and I go out, it becomes this real thing where I am breaking people’s stereotypes and it’s creating these stories. It’s a fictional image, but when we see it [there’s] a real-life transformation. And then tomorrow if you see a cop who happens to have a turban and beard after having seen the cartoon, you’d be like, “Yeah sure, why not?” And this is not something you necessarily verbalize, but subconsciously you make that connection.

[So], it’s the power of images of course, but I think it’s also that behind those images is the shared experience. Because if you look beyond and—I like to call it a story, right?—if you asked somebody where you are from, they will give you an answer. If you ask me, “Just tell me a little bit about yourself,” I’ll say, “My name is Vish, I’m a cartoonist.” But if I tell you my life story, then you’re going to make a lot of connections.

And so the key is sharing those stories. And sometimes you can do that in a single image. And people connect to that.

How would you like to see your art and activism change the world?

One message I have for people is that we can all be superheroes and we can all get out of our comfort zones. There are moments in life when you have to get out on a limb, and I think it’s important that we take the opportunities.

And that’s what I tried with my art. My hope certainly is that my work—my cartoons, my costume play performance, social experiments—can inspire others to realize that there’s a lot of potential they have. Perhaps they can get out of their comfort zone and they can create something, they can make change.

But in shifting people’s perceptions, you might disagree with them, but at the same time you realize, “Wow, they’re able to tell a story through their cartoons.” And my hope is that down the horizon that we can at least say, “Even if you don’t agree with the perspective, that it can exist there and it’s OK for it to exist.” The key for us is to be able to express ourselves and listen to each other.

Use Sikhtoons to discuss religious diversity and identity with your students! You can find a selection of student-friendly ’toons in the Perspectives for a Diverse America Central Text Anthology.