In Montgomery, Alabama, a black-and-white United States flag painted on the side of a downtown building is the background for a 10-by-50-foot mural. Red bleeds from the bottom of the flag. A Black child in the foreground, entwined in police barricade tape, wears a mask that reads, “Are you listening?” The mural features names of victims of police violence in Montgomery. A police officer appears in the left corner, his back to the viewer.

“It was basically saying, all of this time we’ve been yelling, we’ve been screaming, we’ve been shouting,” explains the mural’s artist, Milton Madison, “but it seems we’re speaking the loudest during this time where our mouths are supposed to be covered, or our voices are supposed to be muted because we’ve got masks on. It’s hard to hear, it’s hard to talk, but we’re going to make sure you hear us.”

Public art functions as a tool for social change. For many artists, particularly Black artists, art counters a history of invisibility, shapes public sentiment and changes narratives. With its legacy of activism, Montgomery, Alabama, is perfect for viewing history and mobilizing people to action through public artwork.

Following the murder of George Floyd in May 2020, Madison conceived and completed his dramatic mural in about one week. Two concurrent crises compelled Madison’s work: the endless views of police-shooting deaths on social media timelines and the COVID-19 pandemic, which disproportionately affected Black and Brown communities. The typical grind of everyday work life slowed early in the pandemic, and many people began to contemplate existential problems more seriously. “The coming and going of your day-to-day [routine] didn’t distract you from having to be emotionally affected by it,” Madison recounts, observing that, despite this stillness, violent police interactions continued. “But you still turn around and make time to kill a Black man—out of all that’s going on,” he laments. “You don’t have enough grace or understanding or patience during this time to handle something in a different way.”

During the summer of 2020, artists nationwide created murals, photography, street art and protest signs insisting “We want justice” or “Black Lives Matter.”

“Whatever it was, you saw it big and bold, unashamed,” Madison says. “You saw it so big because it was almost as if you’re screaming visually.”

A Veritable Time Machine

Essential to social justice movements and civic engagement, the arts can counter attempts to dilute or erase history that does not reflect American exceptionalism and white-centered narratives.

“This reemergence or emphasis on the importance of the Black experience in America, after centuries of much more than benign neglect, puts our artistic expressions in the prominent position [they] rightfully deserve. To know a people, one must know their culture in all its permutations.”

—Bill Ford

Artists describe art as a universal language mirroring and influencing life. “The perpetual question with art is, ‘Does art create change that’s reflected in society, or does society project into art what it wants to see in the world?’” says Montgomery-based artist Sunny Paulk. “So it’s always this circular feed, this continuous feed.”

Bill Ford, a veteran Montgomery artist, views art as a vehicle “for conveying the human experience on a visceral level.”

“Sometimes a torrent of words can seem preachy, whereas we’ve all heard ‘one picture is worth a thousand words,’” Ford says. “Social justice is a goal that seeks to enable everyone to receive their due from society; when we can identify with others, it’s a process that is much easier to implement.”

Today’s artistic movement extends from the Black Arts Movement of the 1960s and ’70s, with its focus on Black-centric art in literature, theater, music and the visual arts. Poet Larry Neal referred to the Black Arts Movement as “the aesthetic and spiritual sister of the Black Power concept.”

Alabama State University (ASU) art history professor Mary Soylu, Ph.D., observes that in many ways the Black Arts Movement can be considered the predecessor to the artistic arm of the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement. Going back further in time, Soylu says we can chart this artistic lineage to the work of Black artists of the Works Progress Administration and the Harlem Renaissance. “It’s interesting to observe the artistic connections between the BLM murals and the civil rights murals of the 1960s, particularly the murals that spawned the nationwide mural movement that emerged from Chicago during that time period.”

For documenting the civil rights movement, Ford says photography was the most effective form of art. “The ability to preserve these moments in time without flinching or alteration is invaluable for generations to see—a veritable time machine,” Ford explains. “It is proving to play that same role in the Black Lives Matter movement. … This reemergence or emphasis on the importance of the Black experience in America, after centuries of much more than benign neglect, puts our artistic expressions in the prominent position [they] rightfully deserve. To know a people, one must know their culture in all its permutations.”

Whatever it was, you saw it big and bold, unashamed. You saw it so big because it was almost as if you’re screaming visually.

— Milton Madison

The Art of Storytelling for Civic Engagement

While heartbreaking, Madison’s Montgomery mural is also infused with symbols of hope: colorful butterflies, symbolizing evolution and diversity, fly across the monochromatic flag. Madison says he visualized citizens pushing government representatives to implement policies that help sustain a more just society and, in the mural’s lower right corner, depicted a vibrant group of activists protesting in front of the Alabama Capitol.

The mural received mostly positive feedback and sparked conversations. “You want it to invoke something that might hopefully change the situation for the better,” Madison says.

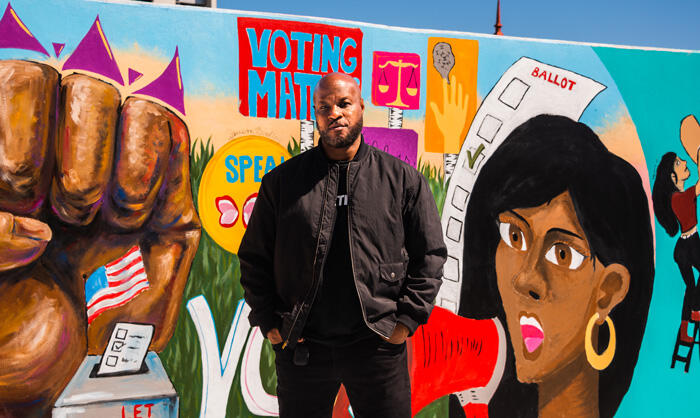

Kalonji Gilchrist, founder of 21 Dreams Arts & Culture, an organization designed to advance creative and cultural arts in Montgomery, entered the art world through film and revolutionary music. He also belongs to We Create Change Alabama, an artist collective addressing the assault on teaching honest history, mass incarceration and voter suppression. The group collaborated with other nonprofit organizations working on those issues to create a series of pop-up exhibitions.

“I realized that power of art to activate or to bring awareness to social issues,” Gilchrist says. “We’re using that power to bring people together and then make sure that they have something to take away. They’re not just walking away without a directive.”

Documenting Montgomery History

Numerous artworks around Montgomery depict stories of justice, injustice, courage and pride. Murals are the most visible examples, from one that uplifts the story of Claudette Colvin to one that celebrates the Montgomery Bus Boycott. These local artists are intentionally foregrounding honest history.

I realized that power of art to activate or to bring awareness to social issues. We’re using that power to bring people together and then make sure that they have something to take away. They’re not just walking away without a directive.

— Kalonji Gilchrist

Other types of art do the same. At the Freedom Rides Museum, a quilt depicts the struggle against segregated travel through the South. Downtown, artist Michelle Browder—who is integral to the city’s art movement—created 15-foot sculptures in homage to enslaved Black women victimized during the development of early gynecological practices. In 2020, Browder helped lead artists in creating a Black Lives Matter street mural at a Montgomery site where enslaved Black people were once auctioned. Completed on Juneteenth, the mural symbolizes that summer’s racial reckoning and brought attention to the city’s role in the slave trade.

Bill Traylor, a former sharecropper born into slavery, and Mose Tolliver—both Black men who received no formal training—are renowned Montgomery artists and part of the city’s rich artistic heritage.

“Some have given Traylor the credit for being the progenitor of modern art in America,” Ford says. “It is most likely that a young Mose Tolliver … took inspiration from seeing Traylor do his thing along Monroe Street, but [Tolliver] didn’t begin to draw steadily until after an accident in a furniture factory disabled him in his late 40s.”

Ford notes new galleries and spaces such as the King’s Canvas, the Urban Dream Fine Arts Center and 21 Dreams Arts & Culture join institutions like the Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts, the Armory Learning Arts Center and the Montgomery Art Guild, presenting various options for artists to create and exhibit their works.

Following the end of slavery and again after school desegregation, public art upheld the “Lost Cause of the Confederacy” myth, which minimized the brutality of slavery and white supremacy in the antebellum South and cast the Confederacy in the best light. The modern art movement works to contest that. Today, Montgomery has Confederate symbols and art representing a more honest history. At City Hall an official seal boasts both the “Birthplace of Civil Rights” and “Cradle of the Confederacy.”

Alana Taylor, an ASU art professor whose work focuses on healing, symbolism and technology, explains that art often moves people to question their thoughts about these Confederate symbols. “You can’t undo your past, but at least you can look at it, evaluate what it was, talk yourself through the transition of what you want it to be, see the benefits of it going this way versus the way you thought it should have been,” Taylor says.

While the city created a committee in 2021 to assess the continued exhibition of Confederate iconography, Alabama state law prohibits the removal, renaming or destruction of memorials, statues, buildings and streets named after those in the Confederacy.

Equal Justice Initiative as an Influence

The Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), a Montgomery-based organization working to end mass incarceration and racial injustice, explores connections between slavery and mass incarceration through its museum content, memorial and art. ASU art history professor Soylu believes EJI’s work motivated local artists to tell—or continue to tell—similar stories.

“Since [EJI’s] National Memorial for Peace and Justice (NMPJ) opened in 2018, something has changed in the art community,” Soylu says. “It’s hard to articulate and profound to witness. In a sense, the art and design of the NMPJ has made history visible to the world, history that has been hidden for so long. This is extraordinary because this region is dominated by Confederate monuments. … Area artists are responding to this unprecedented memorial, and the history and stories it reveals, in a myriad of compelling ways, while also creating a new vision for the future.”

Gilchrist agrees. “There was that awakening,” he says. “Not only do you have those that are just at their core concerned about social issues or create art around social issues, you now have artists that may have been creating art in a different way see the opportunity to express themselves … and then also have it represented in galleries and in murals.”

Portraits of Courage

Art can uplift people whose names we might never know. Last summer, the arts department at ASU received a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts for community programming. For the project, they obtained surveillance photos from the Alabama Law Enforcement Agency of the first attempted Selma to Montgomery March, which resulted in the infamous “Bloody Sunday” attack on marchers. Artists asked community members to help identify participants in the photos, then transformed the photographs into other works of art.

Honoring people for their bravery in protecting democracy can lead viewers to examine their own activism. That’s what happened for Paulk, the Montgomery artist who created the Selma to Montgomery March mural downtown commemorating the march’s 50th anniversary. While working on the Portraits of Courage project, Paulk focused on one boy in the crowd in photos from the march.

“His hands are in his pockets,” she describes. “He’s very anxious, and tense, but so young. So my decision was to paint him on a very narrow canvas in all black and white, surrounded by black, without any background, just a solid color. And just really hone in on who he was, what he’s doing there, how he felt. None of those things I had the answers to. It was just such a small child being part of what became a historic movement, a historic march, but it was so dangerous for him to be there.”

“In painting him, I feel like, shouldn’t I be a braver person than I feel like I can be, because look what he did?” Paulk says. “All these things go into art-making, yet when I’m painting it and you’re looking at it, none of those words are said. It all has to be communicated through the art itself.”

This reemergence or emphasis on the importance of the Black experience in America, after centuries of much more than benign neglect, puts our artistic expressions in the prominent position [they] rightfully deserve.

— Bill Ford

Supporting the Next Generation of Socially Conscious Artists

To uplift and cultivate artists in social justice spaces, communities must value the arts. The 2021 American Academy of Arts and Sciences report Art for Life’s Sake: The Case for Arts Education advocates funding school arts programs, as “there has been a persistent decline in support for arts education, particularly in communities that cannot finance it on their own.”

The lack of such funding, the report indicates, disproportionately affects Black, Indigenous and Latine/x communities, causing “dire effects on the mental health of children and youth.” The report also emphasizes a “causal link between arts education and critical thinking outcomes … increased empathy and higher motivation to engage with arts and culture.”

Alabama artists say funding artistic communities is indispensable. Madison notes he didn’t flourish as an artist until he found community. Without it, Black artists—particularly those who aren’t tied to a postsecondary education art community—don’t feel supported. “We all had the same sentiments that there weren’t places that we could really display our art or that we felt that that culture was being nurtured or created,” Madison recounts.

He imparts the value of art at school, encourages healing through art and aims to elevate students’ moods by painting murals on local school walls. “You see some nice murals in the hallways—that might help change the energy to some kids [who] might be feeling down or sad,” Madison says.

The artists’ work never ends. They should be recognized for their creativity and societal roles as documentarians or historians.

“We haven’t really been so much doing art just for art’s sake, but just really purposeful in building community and advancing community and culture,” Gilchrist says.

Resources

A minilesson from Facing History & Ourselves helps students in grades 6-12 use art to advance social change.

This Learning for Justice webinar, Painting a Just Picture: Art and Activism, helps us understand our history through art.